I Quit! The Tsunami of Burnout Few See

By now, we all know the name of the game is narrative control: we no longer face problems directly and attempt to solve them at their source, we play-act "solutions" that leave the actual problems unrecognized, undiagnosed and unaddressed, on the idea that if cover them up long enough they'll magically go away.

The core narrative control is straightforward: 1) everything's great, and 2) if it's not great, it's going to be great. Whatever's broken is going to get fixed, AI is wunnerful, and so on.

All of these narratives are what I call Happy Stories in the Village of Happy People, a make-believe staging of plucky entrepreneurs minting fortunes, new leadership, technology making our lives better in every way, nonstop binge-worthy entertainment, and look at me, I'm in a selfie-worthy mis en scene that looks natural but was carefully staged to make me look like a winner in the winner-take-most game we're all playing, whether we're aware of it or not.

Meanwhile, off-stage in the real world, people are walking off their jobs: I quit! They're not giving notice, they're just quitting: not coming back from lunch, or resigning without notice.

We collect statistics in the Village of Happy People, but not about real life. We collect stats on GDP "growth," the number of people with jobs, corporate profits, and so on. We don't bother collecting data on why people quit, or why people burn out, or what conditions eventually break them.

Burnout isn't well-studied or understood. It didn't even have a name when I first burned out in the 1980s. It's an amorphous topic because it covers such a wide range of human conditions and experiences.

It's a topic that's implicitly avoided in the Village of Happy People, where the narrative control Happy Story is: it's your problem, not the system's problem, and here's a bunch of psycho-babble "weird tricks" to keep yourself glued together as the unrelenting pressure erodes your resilience until there's none left.

Prisoners of war learn many valuable lessons about the human condition. One is that everyone has a breaking point, everyone cracks. There are no god-like humans; everyone breaks at some point. This process isn't within our control; we can't will ourselves not to crack. We can try, but it's beyond our control. This process isn't predictable. The Strong Leader everyone reckons is unbreakable might crack first, and the milquetoast ordinary person might last the longest.

Those who haven't burned out / been broken have no way to understand the experience. They want to help, and suggest listening to soothing music, or taking a vacation to "recharge." They can't understand that to the person in the final stages of burnout, music is a distraction, and they have no more energy for a vacation than they have for work. Even planning a vacation is beyond their grasp, much less grinding through travel. They're too drained to enjoy anything that's proposed as "rejuvenating."

We're trained to tell ourselves we can do it, that sustained super-human effort is within everyone's reach, "just do it." This is the core cheerleader narrative of the Village of Happy People: we can all overcome any obstacle if we just try harder. That the end-game of trying harder is collapse is taboo.

But we're game until we too collapse. We're mystified by our insomnia, our sudden outbursts, our lapses of focus, and as the circle tightens we jettison whatever we no longer have the energy to sustain, which ironically is everything that sustained us.

We reserve whatever dregs of energy we have for work, and since work isn't sustaining us in any way other than financial, the circle tightens until there's no energy left for anything. So we quit, not because we want to per se, but because continuing is no longer an option, and quitting is a last-ditch effort at self-preservation.

Thanks to the Happy Stories endlessly repeated in the Village of Happy People, we can't believe what's happening to us. We think, this can't be happening to me, I'm resourceful, a problem-solver, a go-getter, I have will power, so why am I banging my head against a wall in frustration? Why can't I find the energy to have friends over?

All these experiences are viewed through the lens of the mental health industry which is blind to the systemic nature of stress and pressure, and so the "fixes" are medications to tamp down what's diagnosed not as burnout but as depression or anxiety, in other words, the symptoms, not the cause.

And so we wonder what's happening to us, as the experience is novel and nobody else seems to be experiencing it. Nobody seems willing to tell the truth, that it's all play-acting: that employers "really care about our employees, you're family," when the reality is we're all interchangeable cogs in the machine that focuses solely on keeping us glued together to do the work.

Why people crack and quit is largely unexplored territory. In my everyday life, three people I don't know quit suddenly. I know about it because their leaving left their workplaces in turmoil, as there are no ready replacements. One person was working two jobs to afford to live in an expensive locale, and the long commute and long hours of her main job became too much. So the other tech is burning out trying to cover her customer base.

In another case, rude / unpleasant customers might have been the last straw, along with a host of other issues. In the moment, the final trigger could be any number of things, but the real issue is the total weight of stress generated by multiple, reinforcing sources of internal and external pressure.

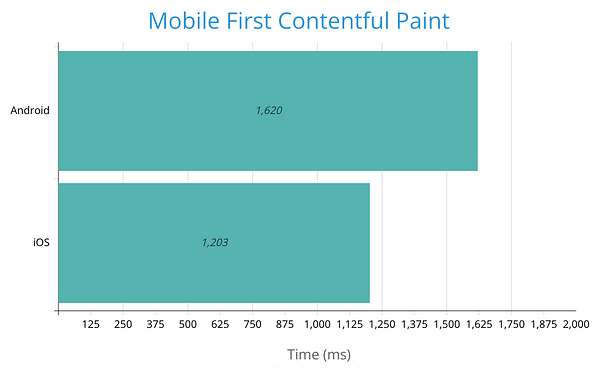

There's a widespread belief that people will take whatever jobs are available when the economy slumps into recession. This presumes people are still able to work. Consider this chart of disability. Few seem interested in exploring this dramatic increase. If anyone mentions it, it's attributed to the pandemic. But is that the sole causal factor?

We're experiencing stagflation, and it may well just be getting started. If history is any guide, costs can continue to rise for quite some time as the purchasing power of wages erodes and asset bubbles deflate. As noted in a previous post, depending on financial fentanyl to keep everything glued together is risky, because we can't tell if the dose is fatal until it's too late.

A significant percentage of the data presented in my posts tells a story that is taboo in the Village of Happy People: everyday life is much harder now, and getting harder. Life was much easier, less overwhelming, more stable and more prosperous in decades past. Wages went farther--a lot farther. I have documented this in dozens of posts.

My Social Security wage records go back 54 years, to 1970, the summer in high school I picked pineapple for Dole. Being a data hound, I laboriously entered the inflation rate as calculated by the Bureau of Labor Statistics (which many see as grossly understating actual inflation) to state each year's earnings in current dollars.

Of my top eight annual earnings, two were from the 1970s, two were from the 1980s, three from the 1990s and only one in the 21st century. Please note that the nominal value of my labor has increased with time / inflation; what we're measuring here is the purchasing power / value of my wages over time.

That the purchasing power of my wages in the 1970s as an apprentice carpenter exceeded almost all the rest of my decades of labor should ring alarm bells. But this too is taboo in the Village of Happy People: of course life is better now because "progress is unstoppable." But is it "progress" if our wages have lost value for 45 years? If precarity on multiple levels is now the norm? If the burdens of shadow work are pushing us over the tipping point?

This is systemic, it's not unique to me. Everyone working in the 70s earned more when measured in purchasing power rather than nominal dollars, and the prosperity of the 80s and 90s was widespread. In the 21st century, not so much: it's a winner-take-most scramble that most of us lose, while the winners get to pull the levers of the narrative control machinery to gush how everything's great, and it's going to get better.

I've burned out twice, once in my early 30s and again in my mid-60s. Overwork, insane commutes (2,400 miles each way), caregiving for an elderly parent, the 7-days-a-week pressures of running a complex business which leaks into one's home life despite every effort to silo it, and so on. I wrote a book about my experiences, Burnout, Reckoning and Renewal, in the hopes that it might help others simply knowing others were sharing their experiences.

What's taboo is to say that the source is the system we inhabit, not our personal inability to manifest god-like powers. The system works fine for the winners who twirl the dials on the narrative control machinery, and they're appalled when they suffer some mild inconvenience when the peasantry doing all the work for them break down and quit.

A tsunami of burnout and quitting, both quiet and loud, is on the horizon, but it's taboo to recognize it or mention it. That the system is broken because it breaks us is the taboo that is frantically enforced at all levels of narrative control.

That's the problem with deploying play-acting as "solutions:" play-acting doesn't actually fix the problems at the source, it simply lets the problems run to failure. The dishes at the banquet of consequences are being served cold because the staff quit: as Johnny Paycheck put it, Take This Job And Shove It.

The peasants don't control the narrative control machinery, and so we ask: cui bono, to whose benefit is the machinery working? The New Nobility, perhaps?

originally posted at

By now, we all know the name of the game is narrative control: we no longer face problems directly and attempt to solve them at their source, we play-act "solutions" that leave the actual problems unrecognized, undiagnosed and unaddressed, on the idea that if cover them up long enough they'll magically go away.

The core narrative control is straightforward: 1) everything's great, and 2) if it's not great, it's going to be great. Whatever's broken is going to get fixed, AI is wunnerful, and so on.

All of these narratives are what I call Happy Stories in the Village of Happy People, a make-believe staging of plucky entrepreneurs minting fortunes, new leadership, technology making our lives better in every way, nonstop binge-worthy entertainment, and look at me, I'm in a selfie-worthy mis en scene that looks natural but was carefully staged to make me look like a winner in the winner-take-most game we're all playing, whether we're aware of it or not.

Meanwhile, off-stage in the real world, people are walking off their jobs: I quit! They're not giving notice, they're just quitting: not coming back from lunch, or resigning without notice.

We collect statistics in the Village of Happy People, but not about real life. We collect stats on GDP "growth," the number of people with jobs, corporate profits, and so on. We don't bother collecting data on why people quit, or why people burn out, or what conditions eventually break them.

Burnout isn't well-studied or understood. It didn't even have a name when I first burned out in the 1980s. It's an amorphous topic because it covers such a wide range of human conditions and experiences.

It's a topic that's implicitly avoided in the Village of Happy People, where the narrative control Happy Story is: it's your problem, not the system's problem, and here's a bunch of psycho-babble "weird tricks" to keep yourself glued together as the unrelenting pressure erodes your resilience until there's none left.

Prisoners of war learn many valuable lessons about the human condition. One is that everyone has a breaking point, everyone cracks. There are no god-like humans; everyone breaks at some point. This process isn't within our control; we can't will ourselves not to crack. We can try, but it's beyond our control. This process isn't predictable. The Strong Leader everyone reckons is unbreakable might crack first, and the milquetoast ordinary person might last the longest.

Those who haven't burned out / been broken have no way to understand the experience. They want to help, and suggest listening to soothing music, or taking a vacation to "recharge." They can't understand that to the person in the final stages of burnout, music is a distraction, and they have no more energy for a vacation than they have for work. Even planning a vacation is beyond their grasp, much less grinding through travel. They're too drained to enjoy anything that's proposed as "rejuvenating."

We're trained to tell ourselves we can do it, that sustained super-human effort is within everyone's reach, "just do it." This is the core cheerleader narrative of the Village of Happy People: we can all overcome any obstacle if we just try harder. That the end-game of trying harder is collapse is taboo.

But we're game until we too collapse. We're mystified by our insomnia, our sudden outbursts, our lapses of focus, and as the circle tightens we jettison whatever we no longer have the energy to sustain, which ironically is everything that sustained us.

We reserve whatever dregs of energy we have for work, and since work isn't sustaining us in any way other than financial, the circle tightens until there's no energy left for anything. So we quit, not because we want to per se, but because continuing is no longer an option, and quitting is a last-ditch effort at self-preservation.

Thanks to the Happy Stories endlessly repeated in the Village of Happy People, we can't believe what's happening to us. We think, this can't be happening to me, I'm resourceful, a problem-solver, a go-getter, I have will power, so why am I banging my head against a wall in frustration? Why can't I find the energy to have friends over?

All these experiences are viewed through the lens of the mental health industry which is blind to the systemic nature of stress and pressure, and so the "fixes" are medications to tamp down what's diagnosed not as burnout but as depression or anxiety, in other words, the symptoms, not the cause.

And so we wonder what's happening to us, as the experience is novel and nobody else seems to be experiencing it. Nobody seems willing to tell the truth, that it's all play-acting: that employers "really care about our employees, you're family," when the reality is we're all interchangeable cogs in the machine that focuses solely on keeping us glued together to do the work.

Why people crack and quit is largely unexplored territory. In my everyday life, three people I don't know quit suddenly. I know about it because their leaving left their workplaces in turmoil, as there are no ready replacements. One person was working two jobs to afford to live in an expensive locale, and the long commute and long hours of her main job became too much. So the other tech is burning out trying to cover her customer base.

In another case, rude / unpleasant customers might have been the last straw, along with a host of other issues. In the moment, the final trigger could be any number of things, but the real issue is the total weight of stress generated by multiple, reinforcing sources of internal and external pressure.

There's a widespread belief that people will take whatever jobs are available when the economy slumps into recession. This presumes people are still able to work. Consider this chart of disability. Few seem interested in exploring this dramatic increase. If anyone mentions it, it's attributed to the pandemic. But is that the sole causal factor?

We're experiencing stagflation, and it may well just be getting started. If history is any guide, costs can continue to rise for quite some time as the purchasing power of wages erodes and asset bubbles deflate. As noted in a previous post, depending on financial fentanyl to keep everything glued together is risky, because we can't tell if the dose is fatal until it's too late.

A significant percentage of the data presented in my posts tells a story that is taboo in the Village of Happy People: everyday life is much harder now, and getting harder. Life was much easier, less overwhelming, more stable and more prosperous in decades past. Wages went farther--a lot farther. I have documented this in dozens of posts.

My Social Security wage records go back 54 years, to 1970, the summer in high school I picked pineapple for Dole. Being a data hound, I laboriously entered the inflation rate as calculated by the Bureau of Labor Statistics (which many see as grossly understating actual inflation) to state each year's earnings in current dollars.

Of my top eight annual earnings, two were from the 1970s, two were from the 1980s, three from the 1990s and only one in the 21st century. Please note that the nominal value of my labor has increased with time / inflation; what we're measuring here is the purchasing power / value of my wages over time.

That the purchasing power of my wages in the 1970s as an apprentice carpenter exceeded almost all the rest of my decades of labor should ring alarm bells. But this too is taboo in the Village of Happy People: of course life is better now because "progress is unstoppable." But is it "progress" if our wages have lost value for 45 years? If precarity on multiple levels is now the norm? If the burdens of shadow work are pushing us over the tipping point?

This is systemic, it's not unique to me. Everyone working in the 70s earned more when measured in purchasing power rather than nominal dollars, and the prosperity of the 80s and 90s was widespread. In the 21st century, not so much: it's a winner-take-most scramble that most of us lose, while the winners get to pull the levers of the narrative control machinery to gush how everything's great, and it's going to get better.

I've burned out twice, once in my early 30s and again in my mid-60s. Overwork, insane commutes (2,400 miles each way), caregiving for an elderly parent, the 7-days-a-week pressures of running a complex business which leaks into one's home life despite every effort to silo it, and so on. I wrote a book about my experiences, Burnout, Reckoning and Renewal, in the hopes that it might help others simply knowing others were sharing their experiences.

What's taboo is to say that the source is the system we inhabit, not our personal inability to manifest god-like powers. The system works fine for the winners who twirl the dials on the narrative control machinery, and they're appalled when they suffer some mild inconvenience when the peasantry doing all the work for them break down and quit.

A tsunami of burnout and quitting, both quiet and loud, is on the horizon, but it's taboo to recognize it or mention it. That the system is broken because it breaks us is the taboo that is frantically enforced at all levels of narrative control.

That's the problem with deploying play-acting as "solutions:" play-acting doesn't actually fix the problems at the source, it simply lets the problems run to failure. The dishes at the banquet of consequences are being served cold because the staff quit: as Johnny Paycheck put it, Take This Job And Shove It.

The peasants don't control the narrative control machinery, and so we ask: cui bono, to whose benefit is the machinery working? The New Nobility, perhaps?

originally posted at

I Quit! The Tsunami of Burnout Few See

That's the problem with deploying play-acting as "solutions:" play-acting doesn't actually fix the problems at the source, it simply lets th...

Stacker News

I Quit! The Tsunami of Burnout Few See \ stacker news

By now, we all know the name of the game is narrative control: we no longer face problems directly and attempt to solve them at their source, we pl...