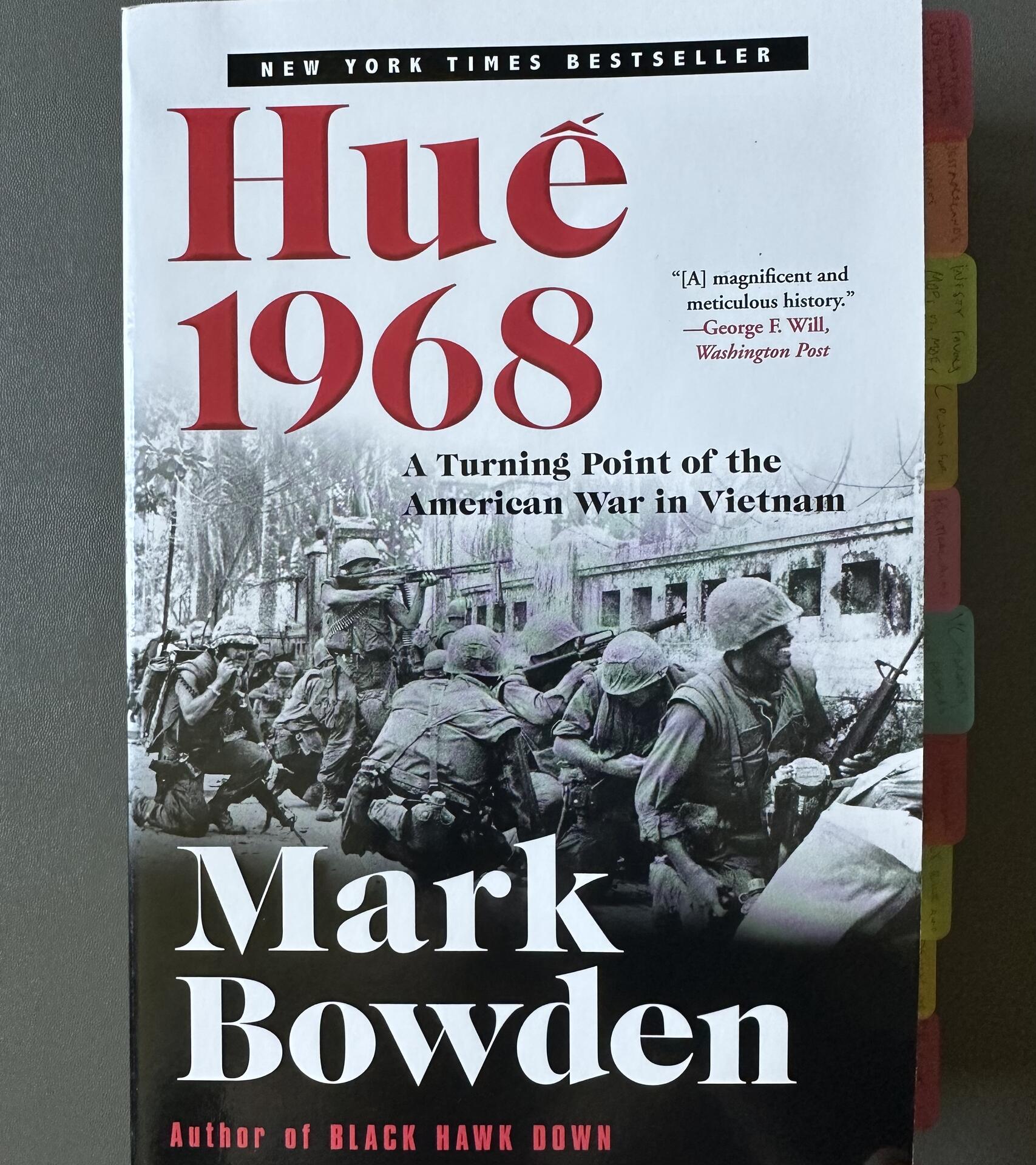

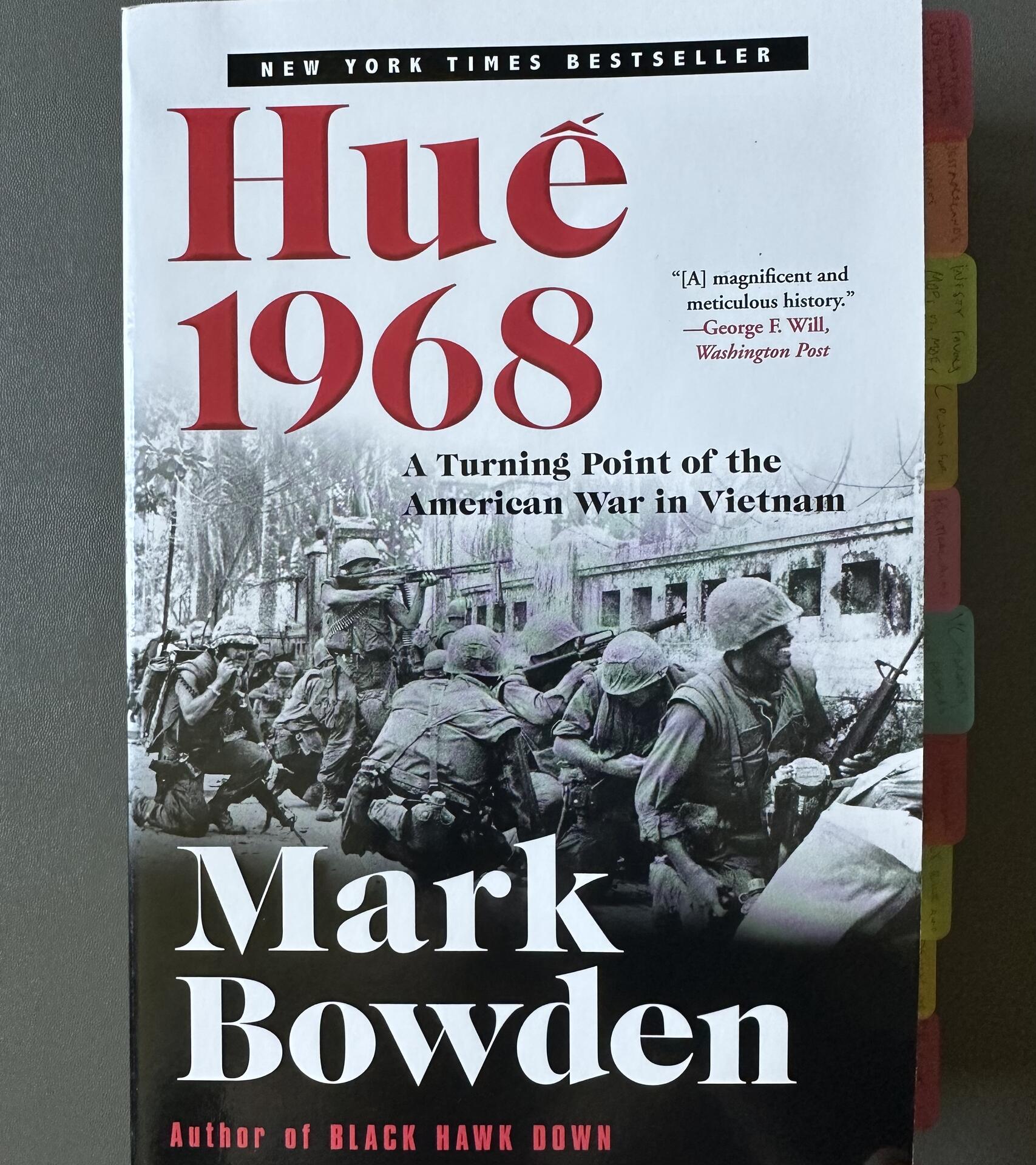

“Huế 1968: A Turning Point of the American War in Vietnam” by Mark Bowden

⭐️⭐️⭐️⭐️

The same journalist who captured the story of Mogadishu in “Black Hawk Down” wrote this incredibly detailed account of what was arguably the Vietnam War’s bloodiest battle. As the historical capital of a once unified Vietnam, Huế is situated just south of the former DMZ separating what was North & South Vietnam. In 1968, Huế was home to one of the Tet Offensive’s pivotal battles as well as some of the worst American blunders of the war. Bowden paints an incredibly detailed portrait of the battle’s horrors thanks to impressive first-hand accounts from both sides of the conflict. The death and destruction witnessed is made more frustrating by the clear folly of American leaders whose “deadly disbelief” of ground truths cost countless lives. Bowden’s book serves up lessons on humility that we ought to internalize today.