Are ETFs better than self custody? Currency Wars 2 and VR Class (1 min video)

Sebcurity

sebcurity@nostrcheck.me

npub13z7h...xcwf

anarcho capitalist

stacking sats

eating meat

chilling on nostr

Fragile Telegram is down.

Anti-fragile Nostr is always up.

Nostr = Hydra

Seasteading! Like Waterworld?

Will Seasteads just end up like Waterworld?

Waterworld is what you imagine when you bring your land-based assumptions to the ocean. The movie opens to a world in which fresh water is a precious commodity.

But the first single-family seastead produced 60 gallons of fresh water every day, powered by just a few solar panels. On many ships today, desalinated seawater is used for drinking, showering, cooking, laundering, and even swimming.

Soil is also precious commodity in Waterworld, but why? 10,000 species of edible algae don’t need soil to grow.

Seasteaders plan to grow ocean crops along with fish and shellfish farms to create closed-loop food systems that improve water quality.

The bad guys in Waterworld, the Smokers, control an oil tanker. It’s the source of their wealth. The Smokers would need refineries to convert crude crude oil into gasoline. But that’s only a land problem.

On the ocean, energy is everywhere in the form of wind, wave, and solar power.

Algae fuel and solar energy are already powering boats and drones. The technology is getting cheaper and should beat the price point of oil long before humanity evolves gills.

OTEC is already proven green technology that uses the temperature difference between deep cold water and warm surface water to run a heat engine to produce electricity. The first OTEC plant is providing power to homes in Hawaii right now.

And why is everybody in Waterworld fighting? Wars on land are often fought to control resources.

On the sea, there is little reason for war.

Cruise ships are self-governing societies that have sailed the seas for decades, and so far battles between cruise ships have not emerged as a business model. Instead, they compete to serve superior governance to their customers and employees who are free to choose among them.

Next time somebody asks you, “Haven’t you seen Waterworld?” ask them, “Have you sailed with Disney cruises?”

If you’d like to learn more about civil society emerging on more another two-thirds of of the earth’s surface, go to Seastading.org and read Seasteading: How Floating Nations Will Restore the Environment, Enrich the Poor, Cure the Sick, and Liberate Humanity from Politicians.

Created by Joe Quirk, Jackson Sullivan, and Carly Jackson.

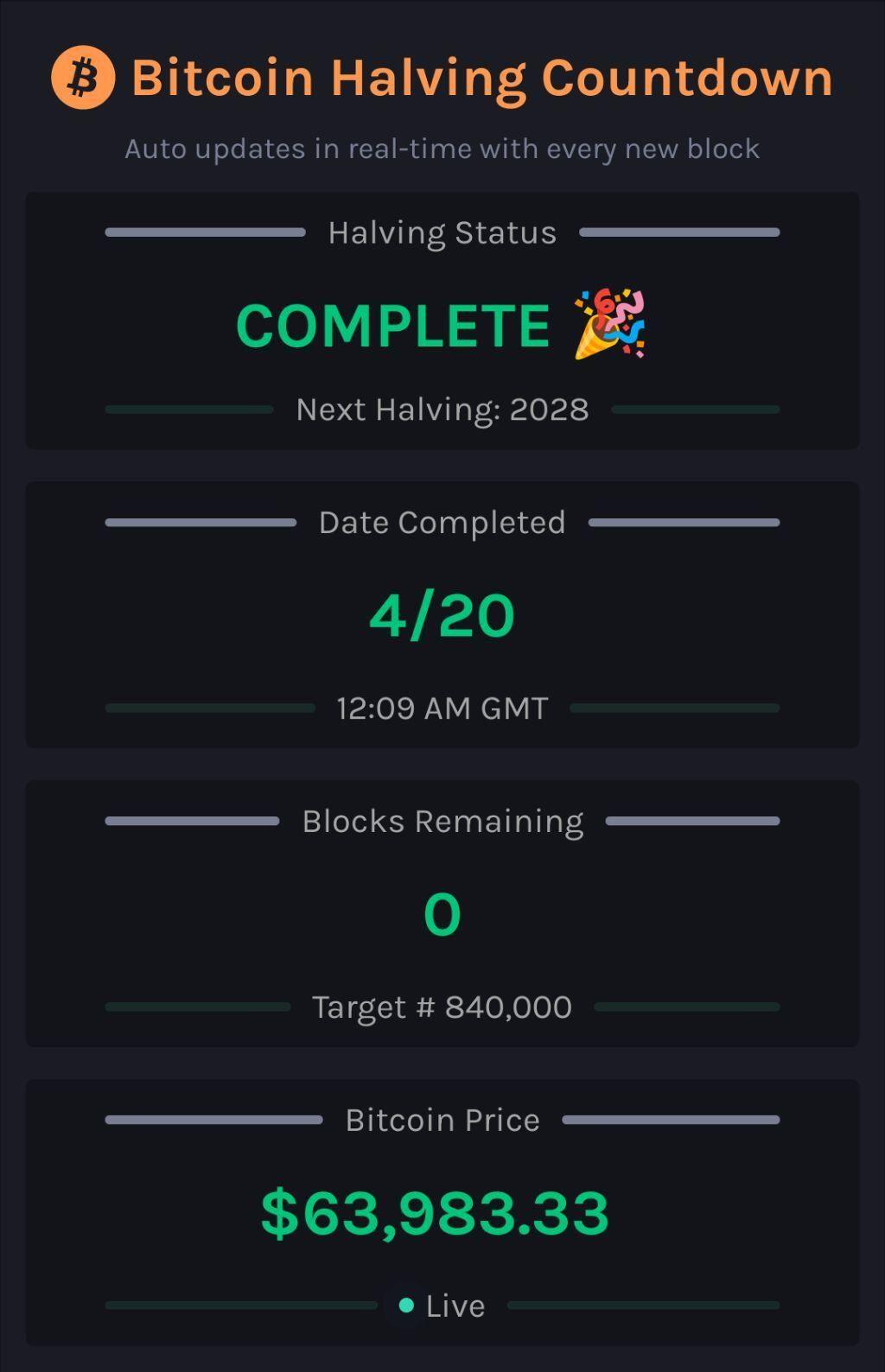

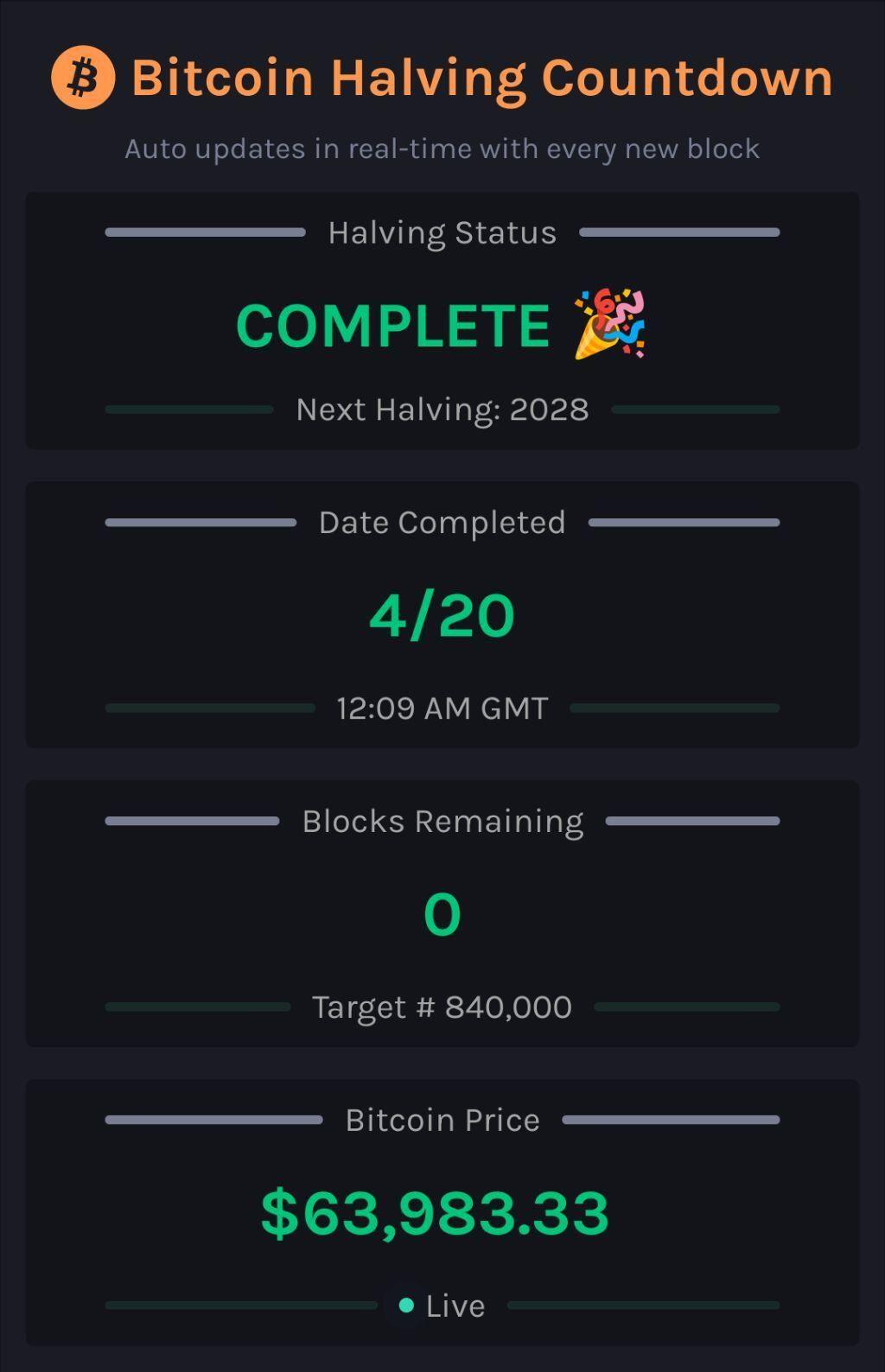

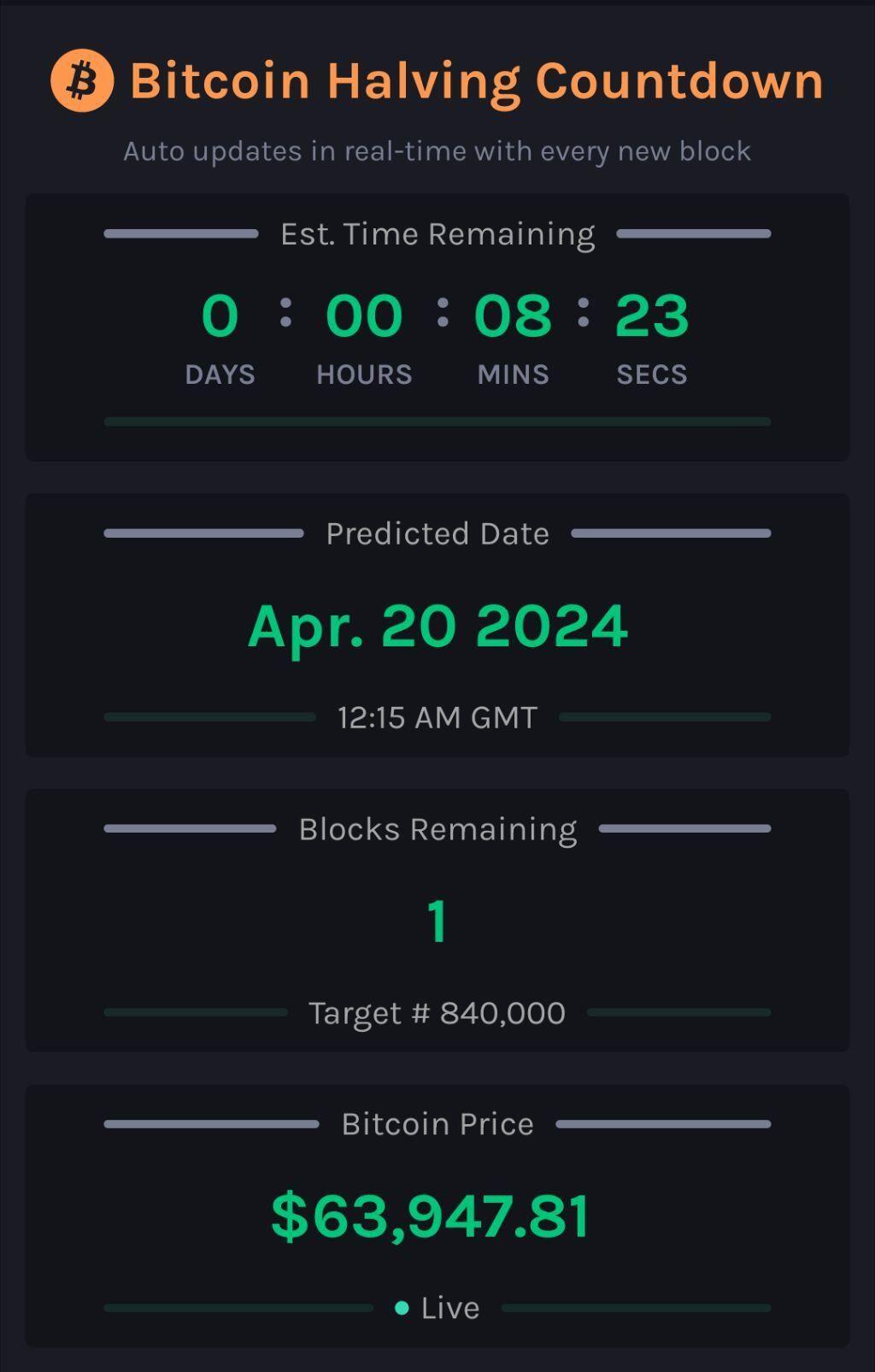

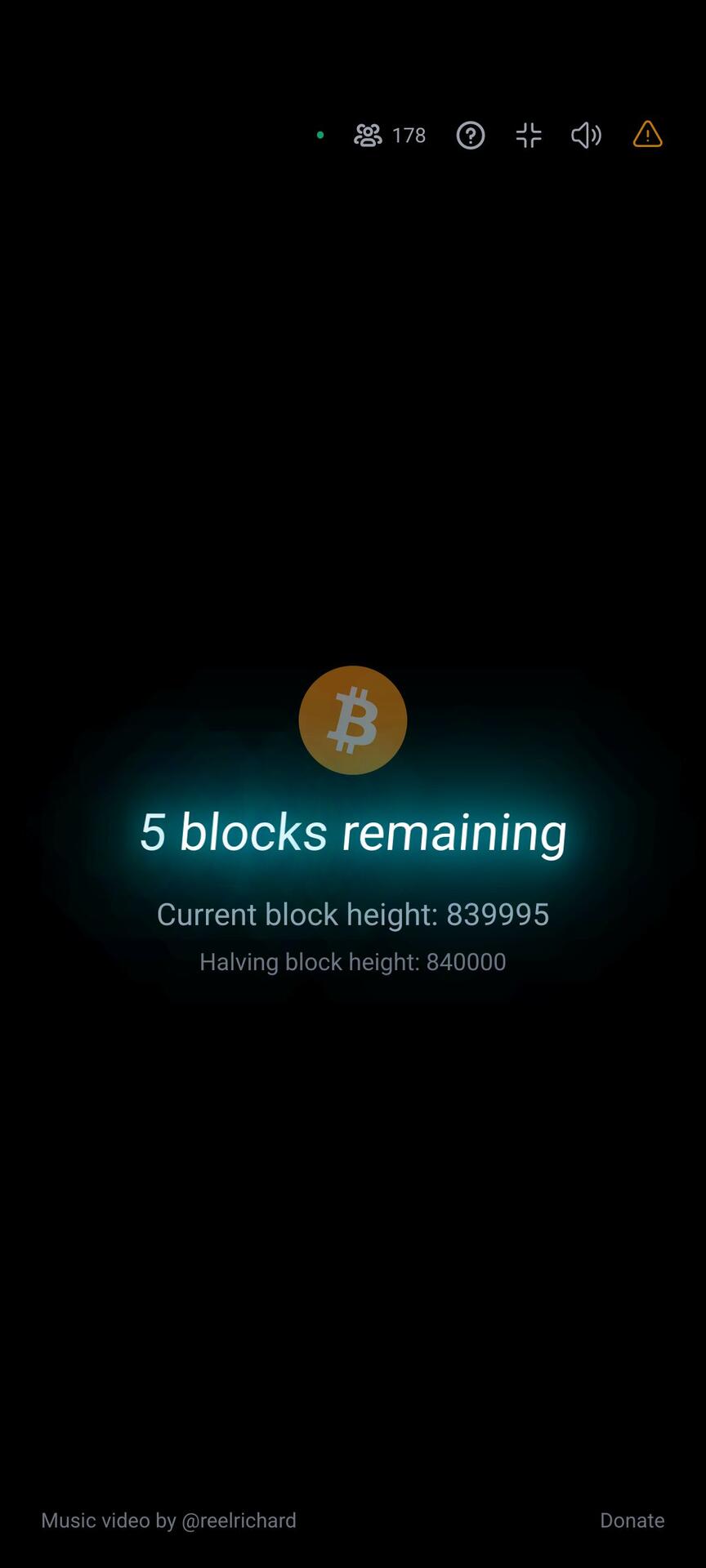

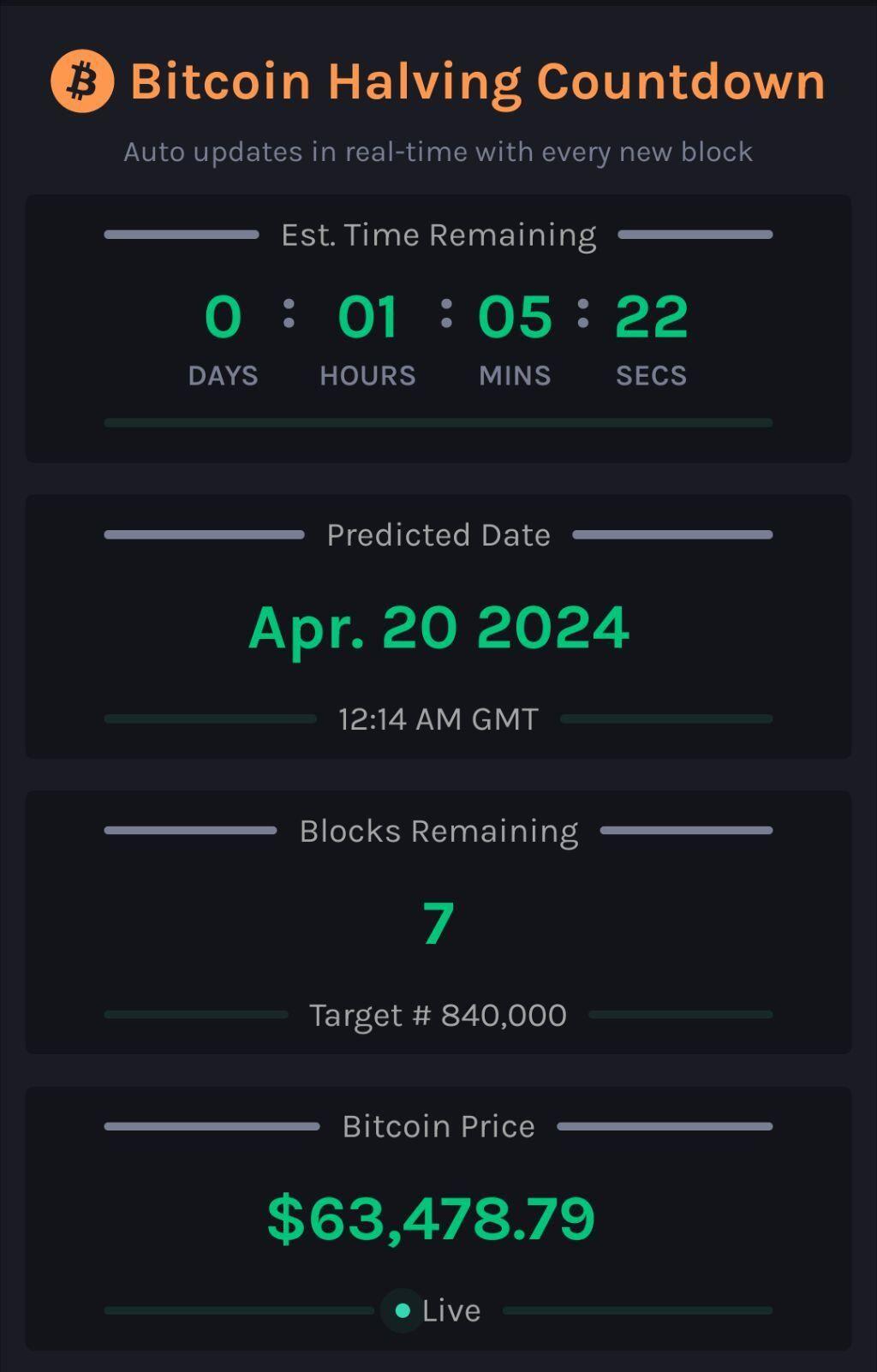

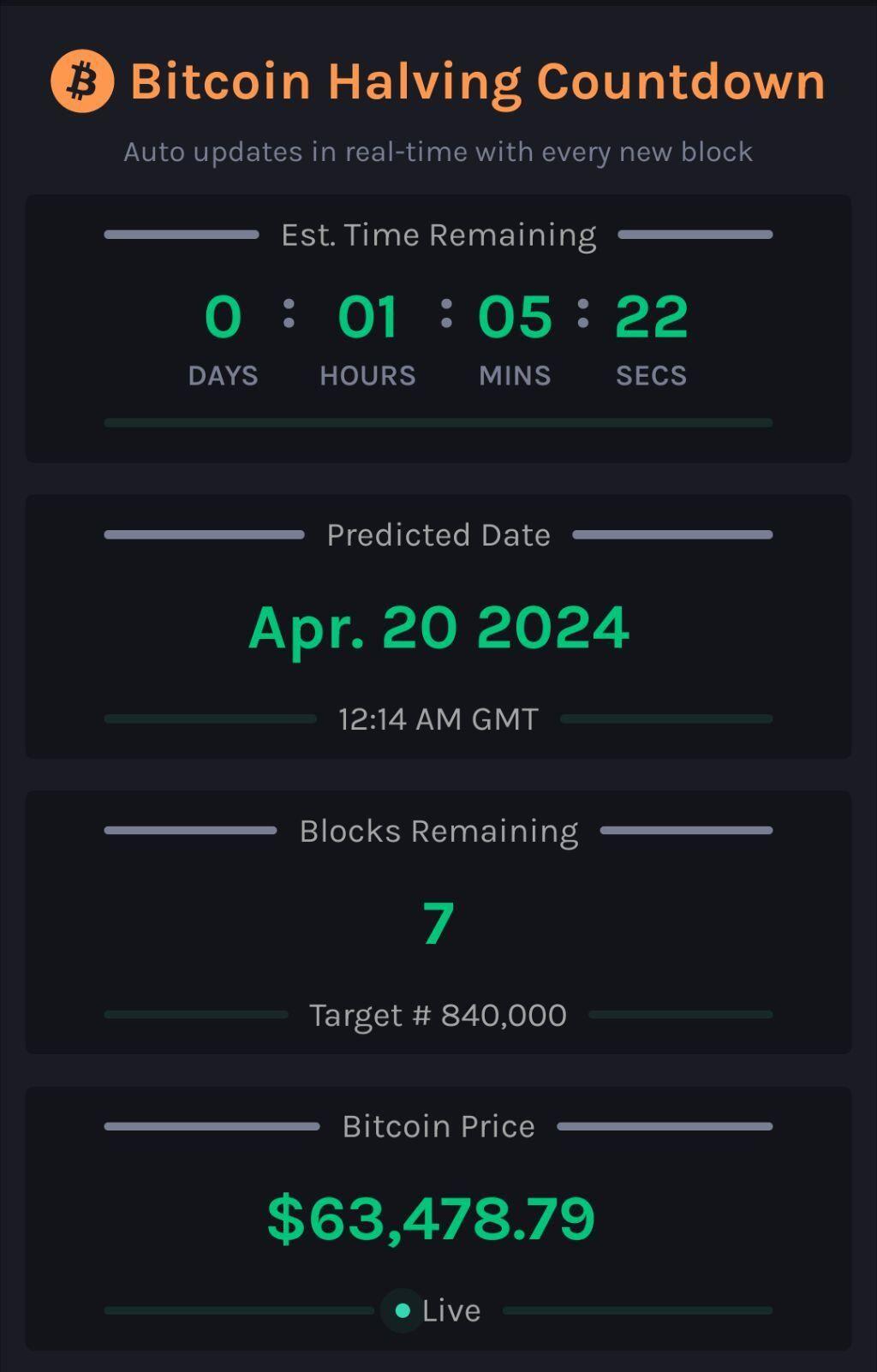

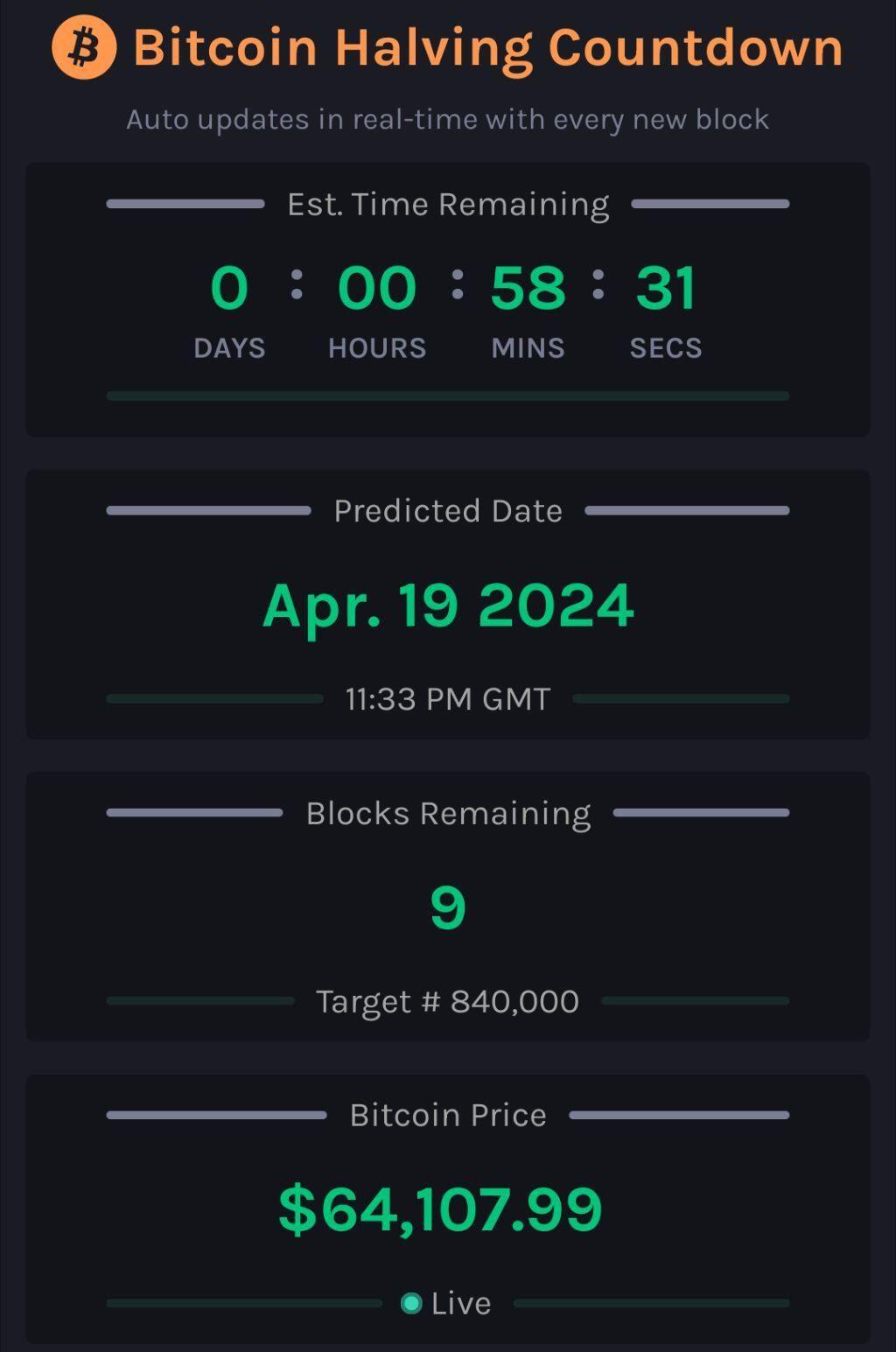

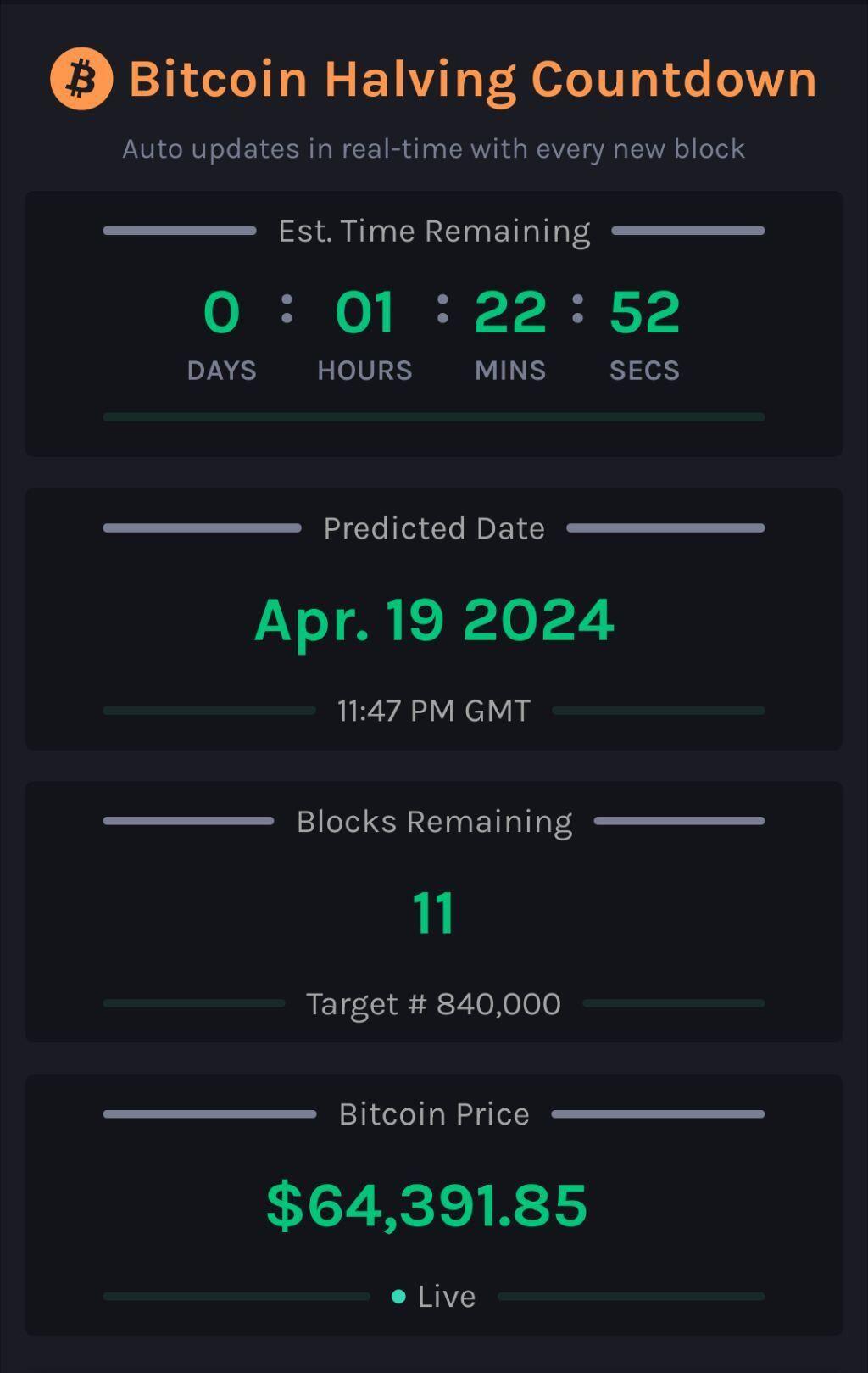

!!! HAPPY HALVING !!!

#countdown #countdownstr #Bitcoin #Bitcoinhalving

Bitcoin Halving Countdown Live

This tool allows you to track the Bitcoin Halving event in real-time with an automatically updating countdown. It updates continuously to reflect t...

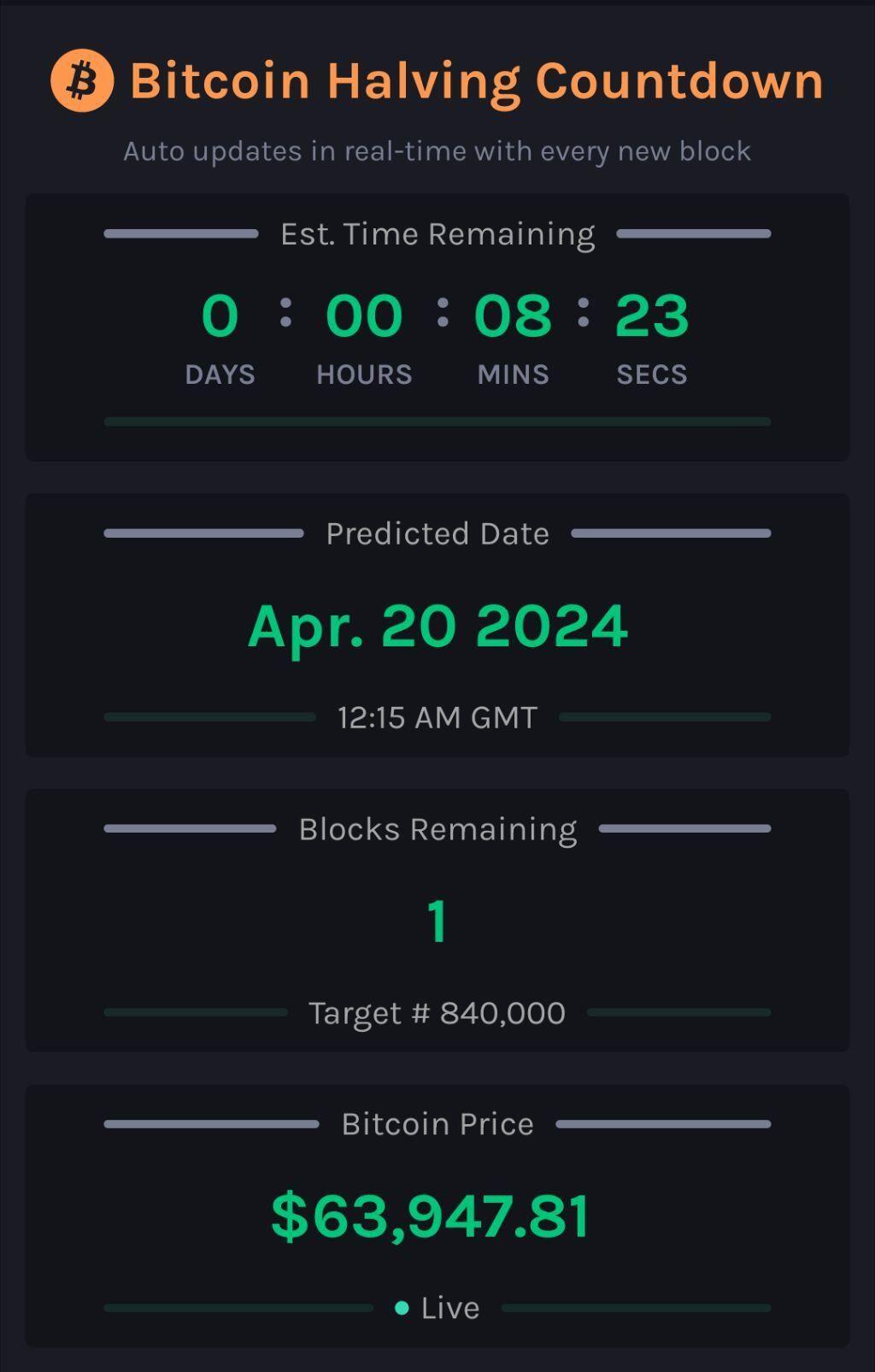

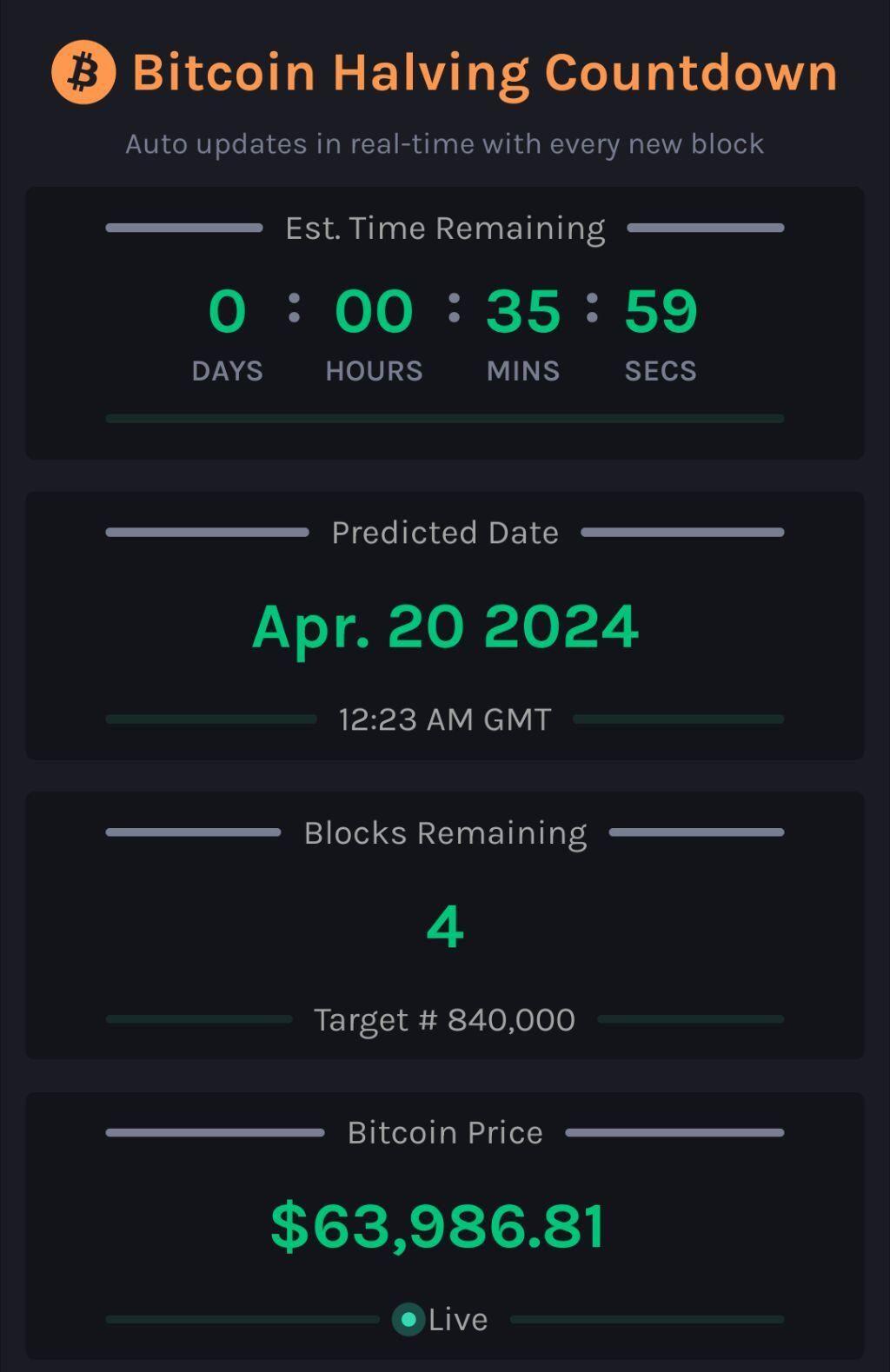

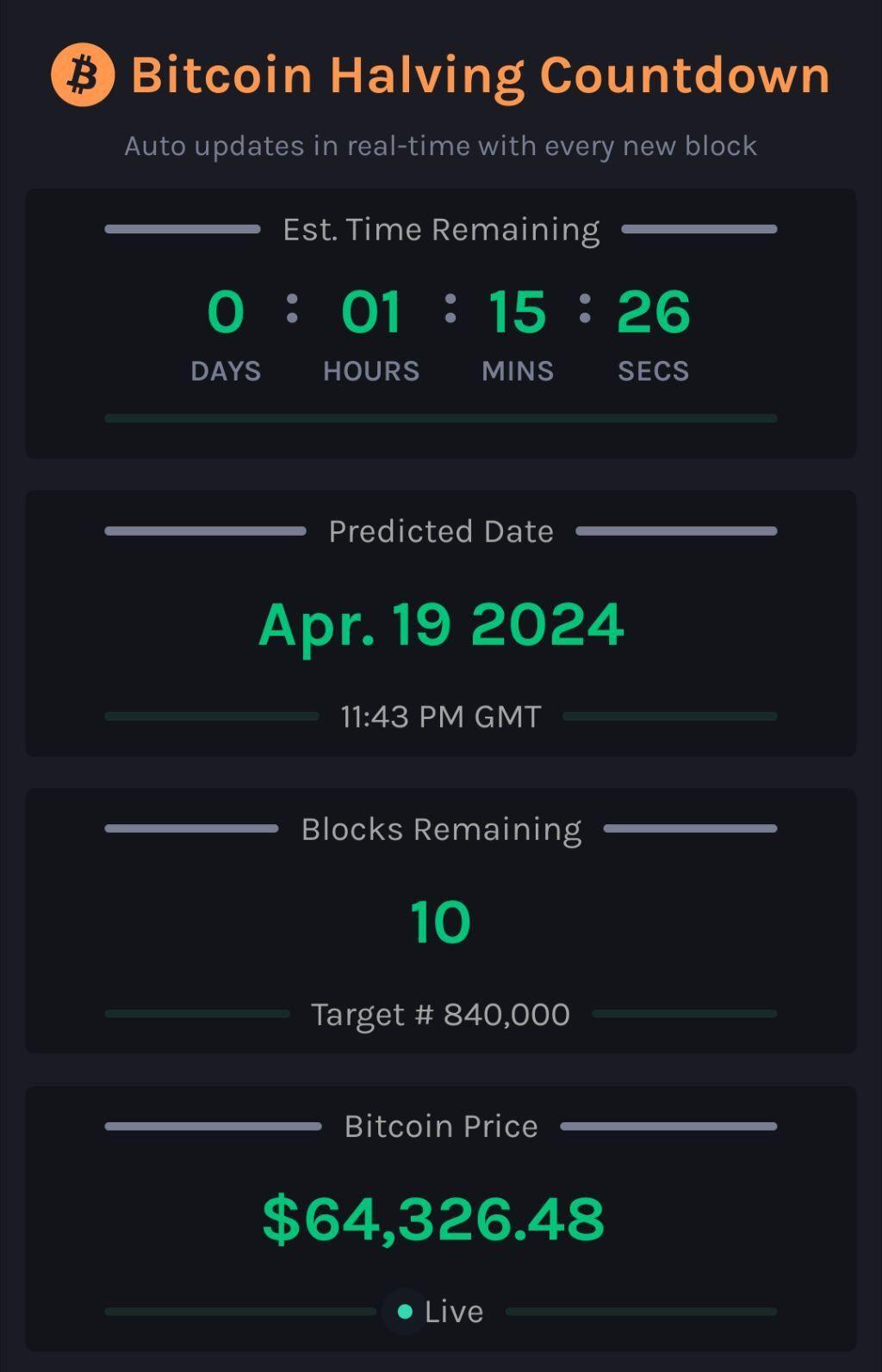

!!! 1 !!!

#countdown #countdownstr #Bitcoin #Bitcoinhalving

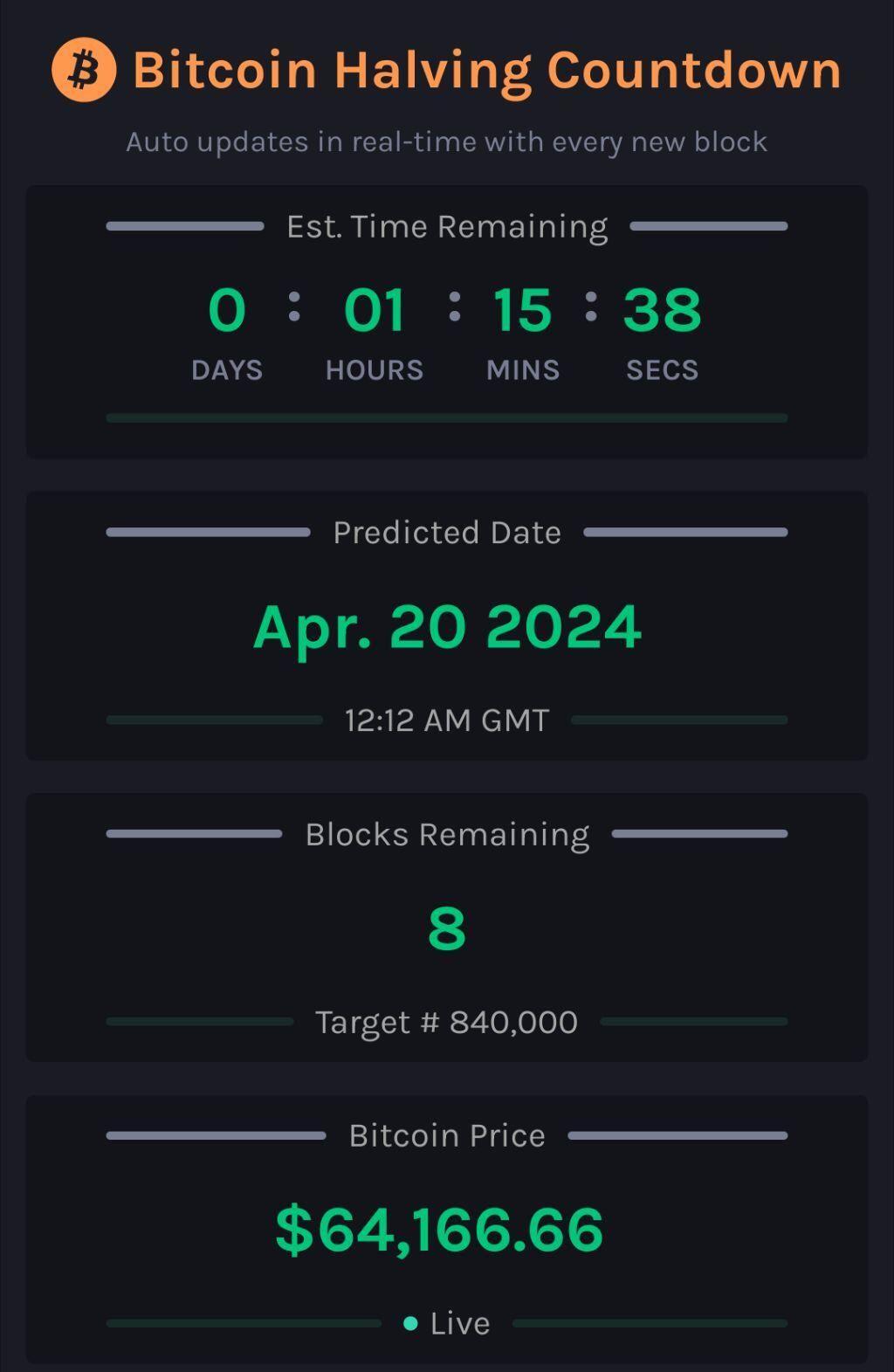

Bitcoin Halving Countdown Live

This tool allows you to track the Bitcoin Halving event in real-time with an automatically updating countdown. It updates continuously to reflect t...

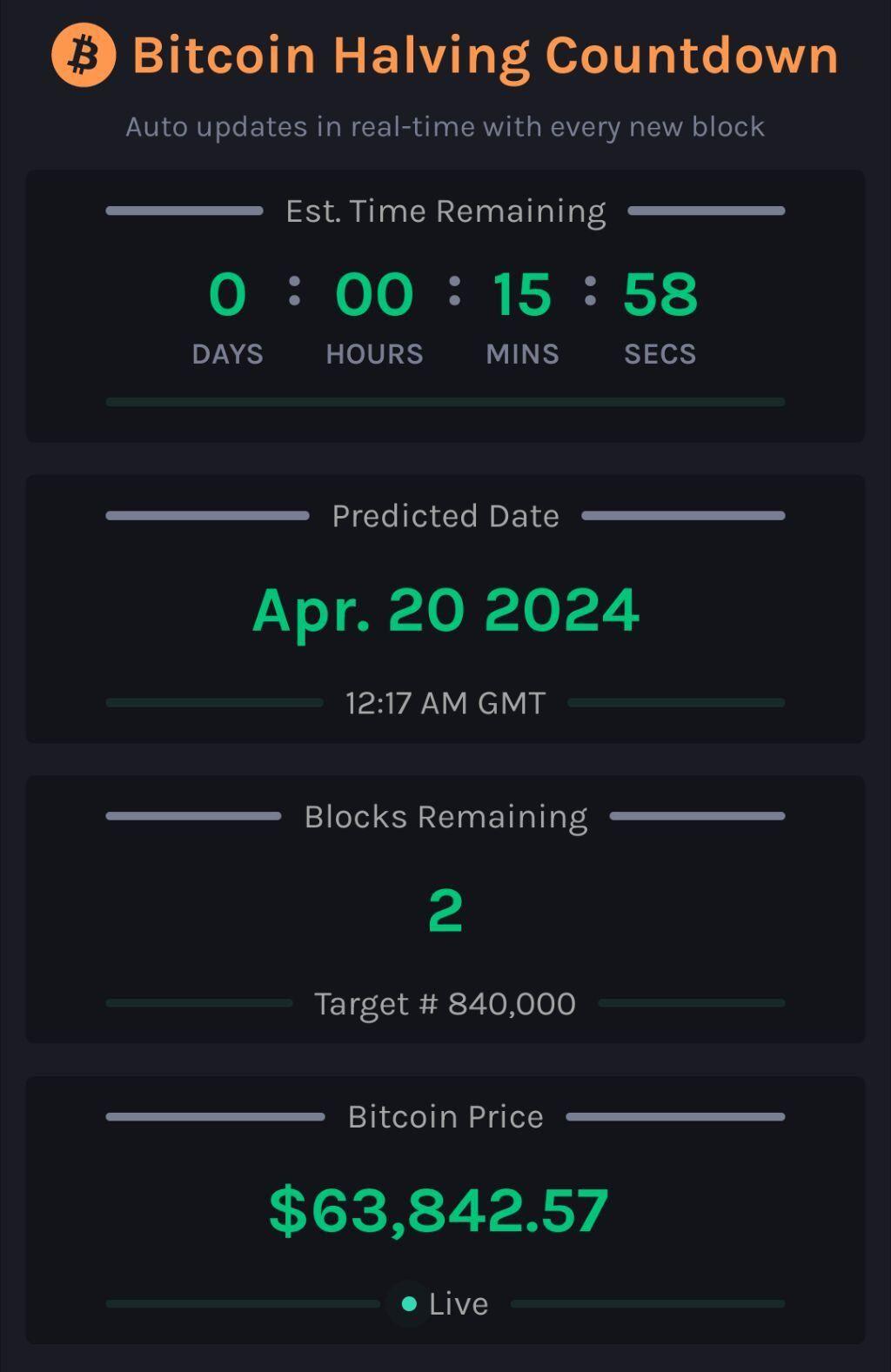

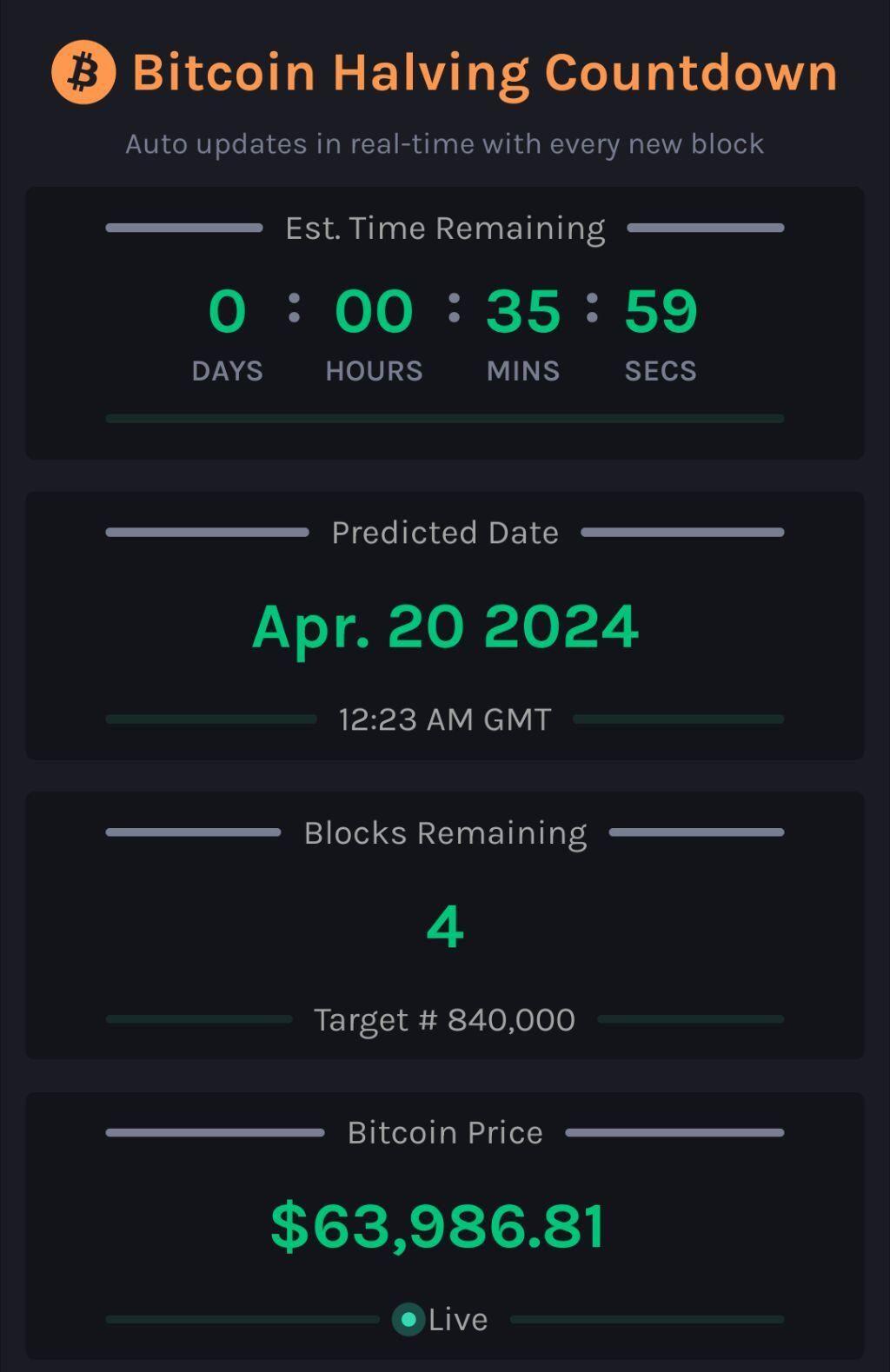

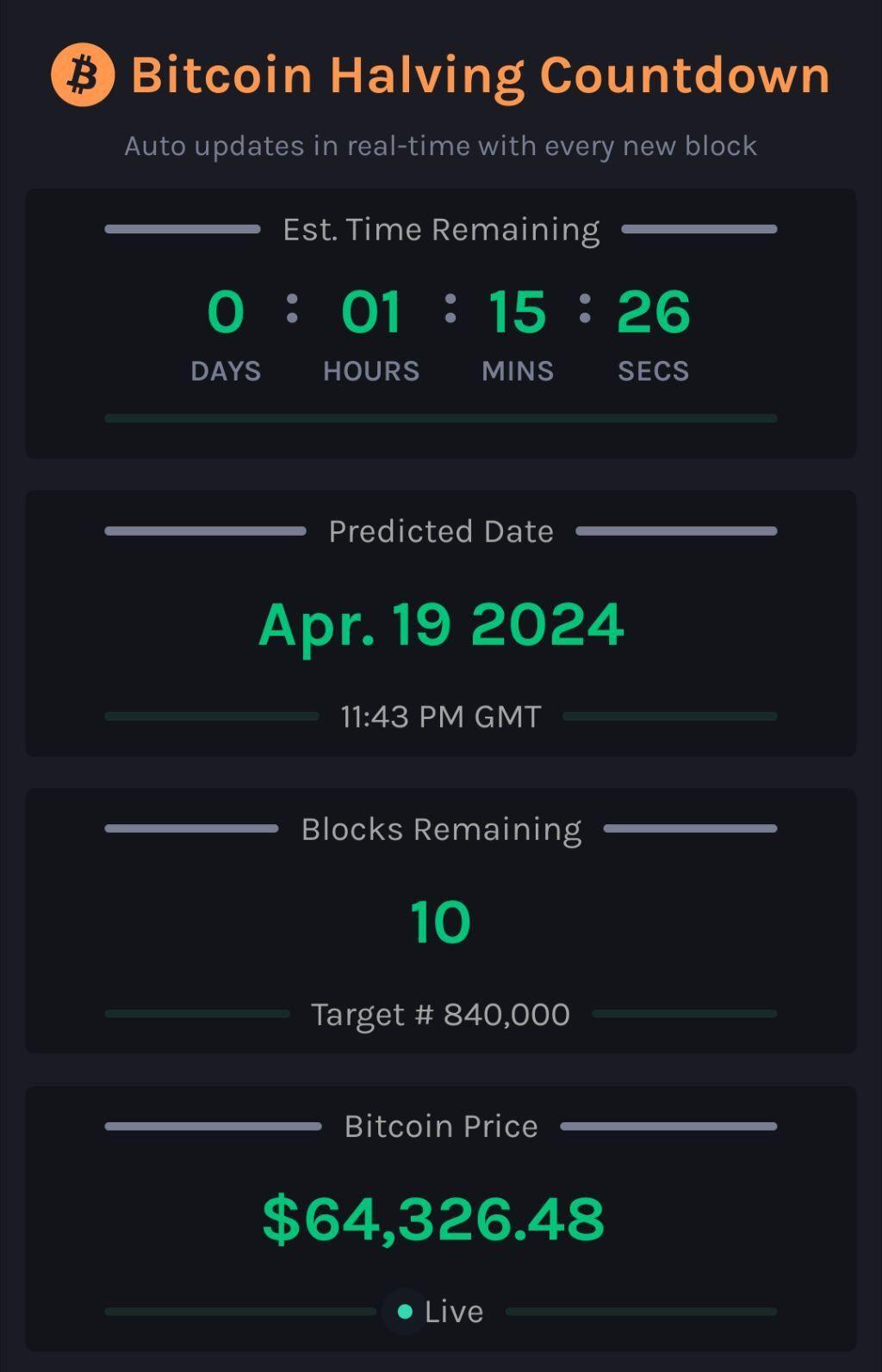

2!

#countdown #countdownstr #Bitcoin #Bitcoinhalving

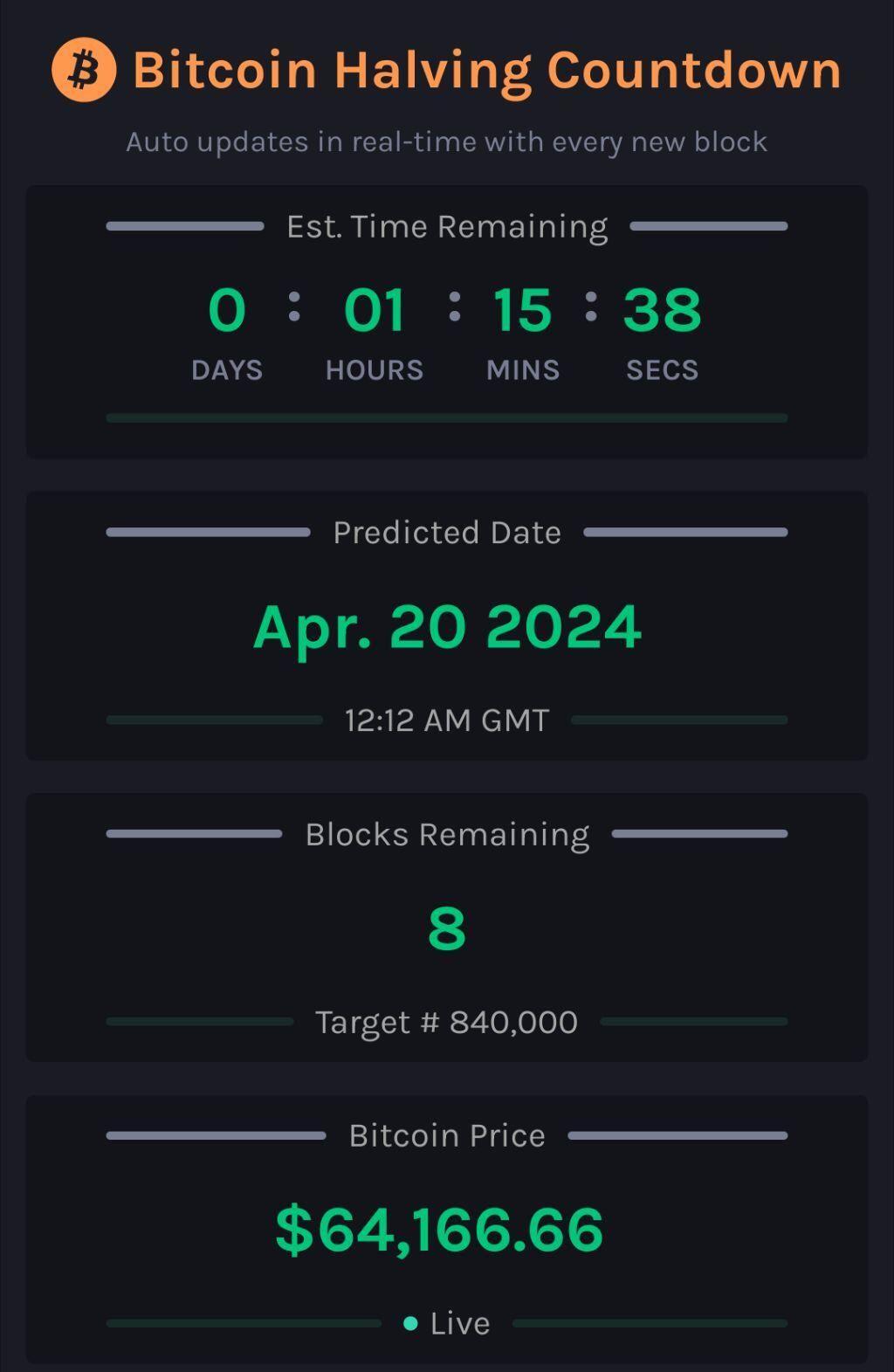

Bitcoin Halving Countdown Live

This tool allows you to track the Bitcoin Halving event in real-time with an automatically updating countdown. It updates continuously to reflect t...

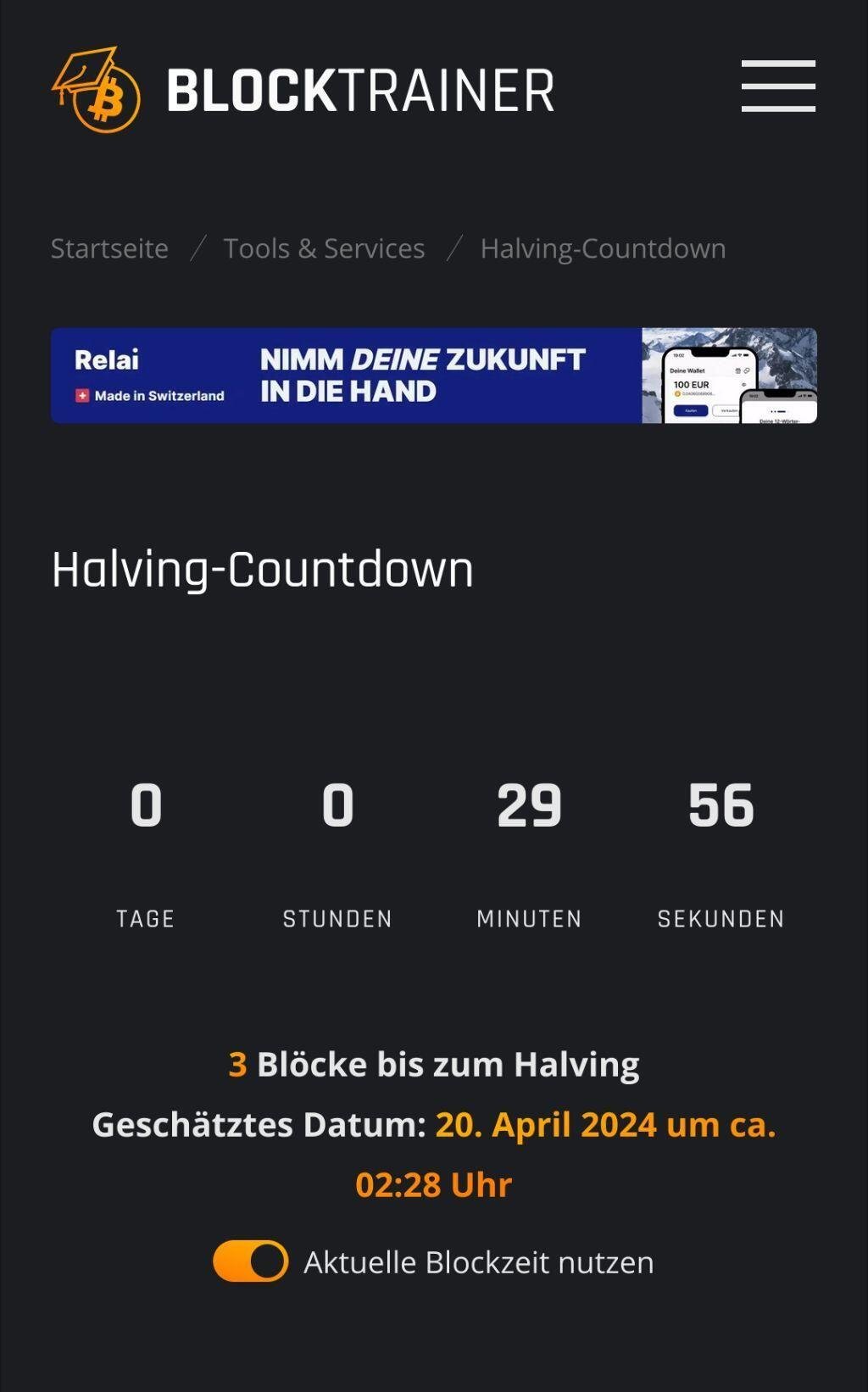

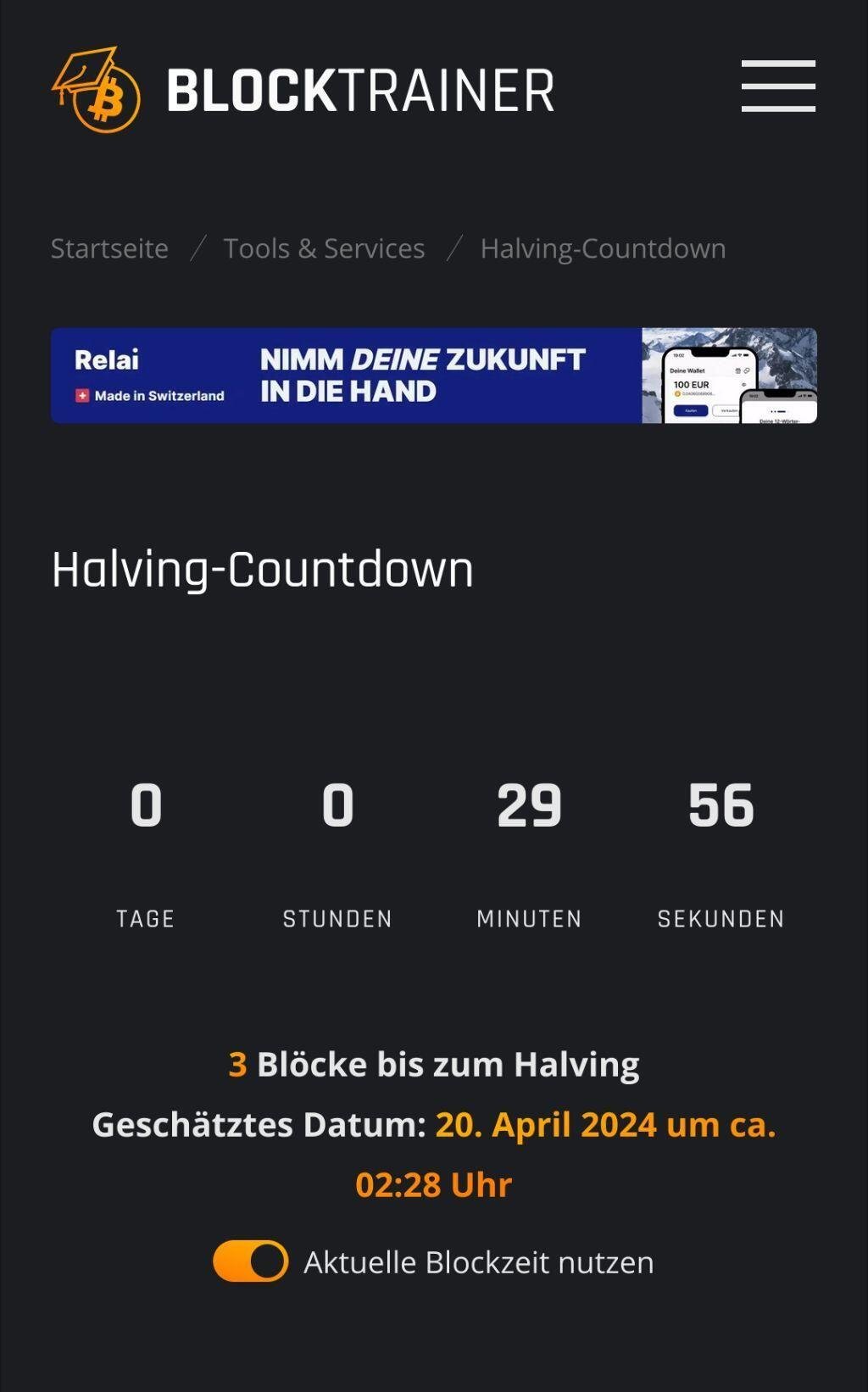

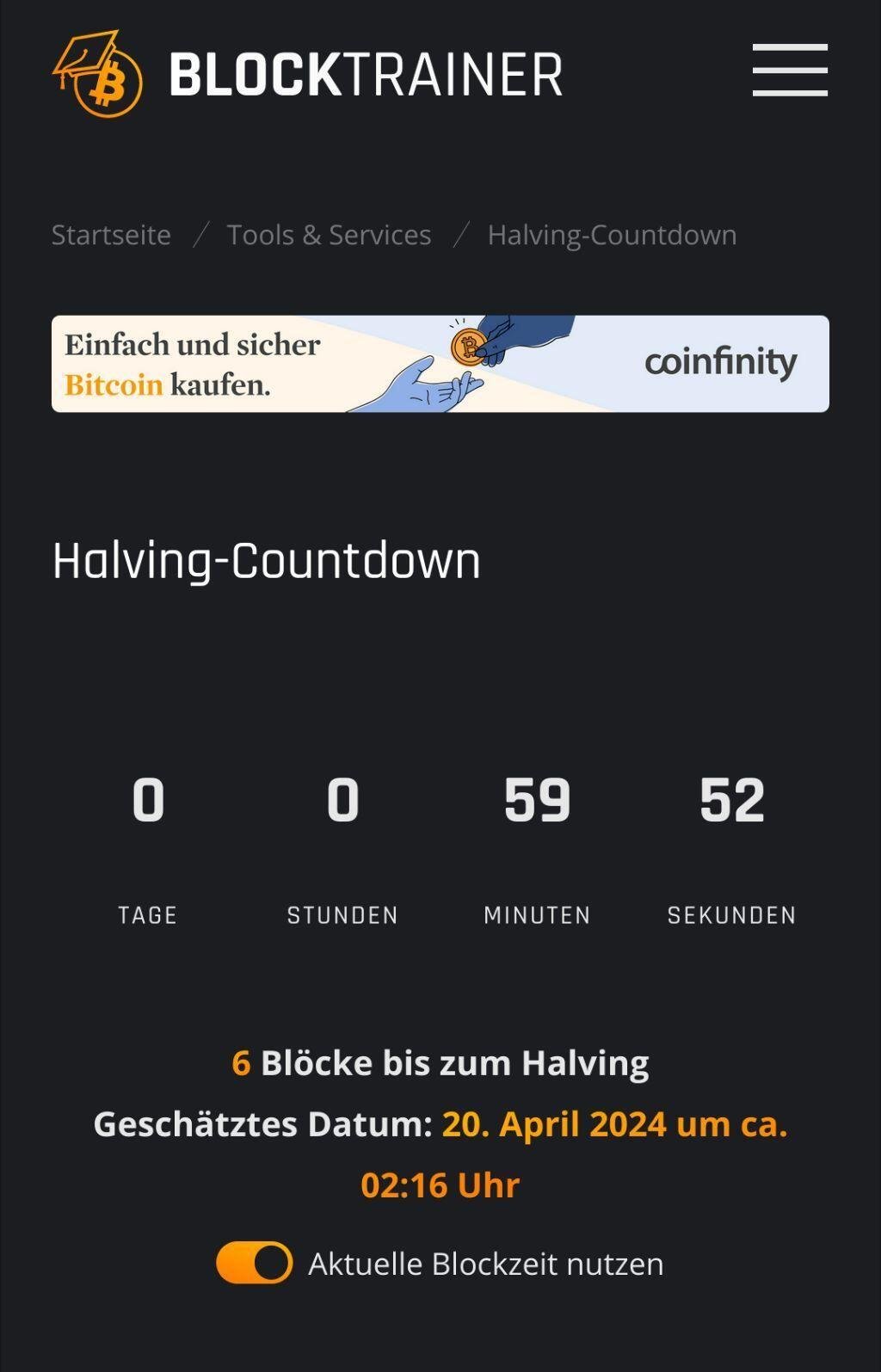

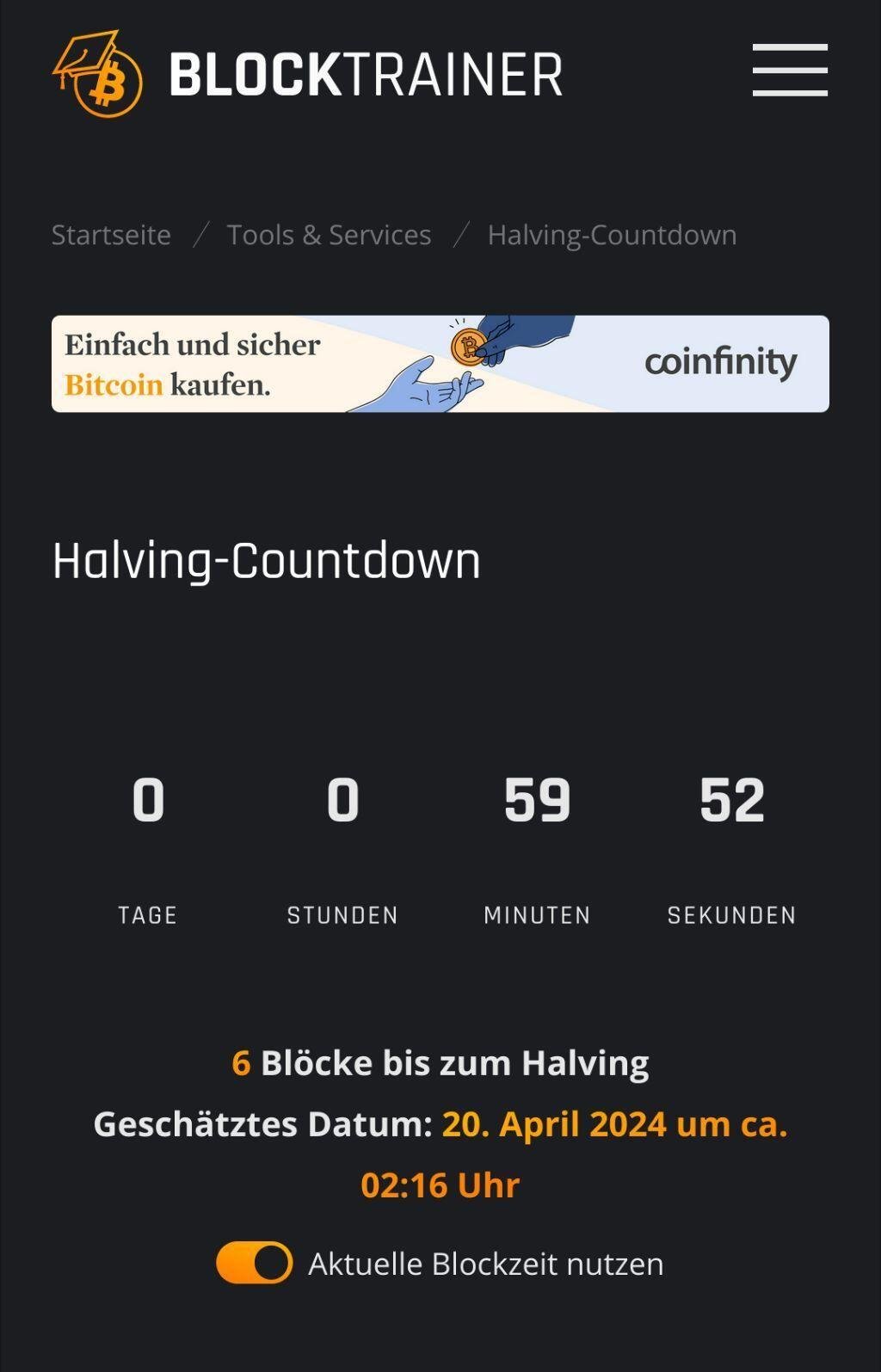

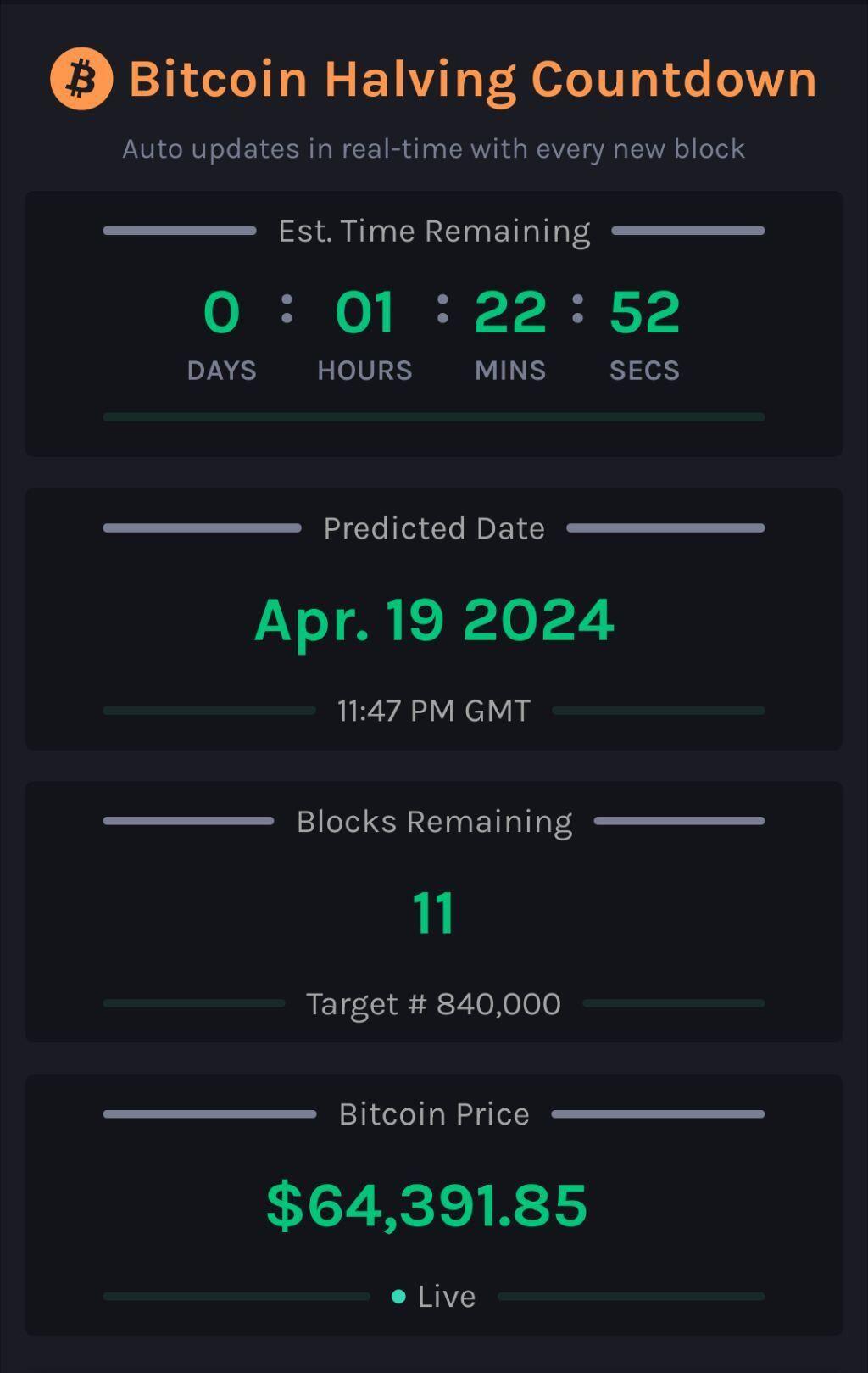

3!

#countdown #countdownstr #Bitcoin #Bitcoinhalving

Blocktrainer - Bitcoin Bildung & News

Halving-Countdown

Verfolge in Echtzeit den Countdown bis zum nächsten Bitcoin-Halving, wenn die Anzahl neuer Bitcoin pro Block halbiert wird!

4!

#countdown #countdownstr #Bitcoin #Bitcoinhalving

Bitcoin Halving Countdown Live

This tool allows you to track the Bitcoin Halving event in real-time with an automatically updating countdown. It updates continuously to reflect t...

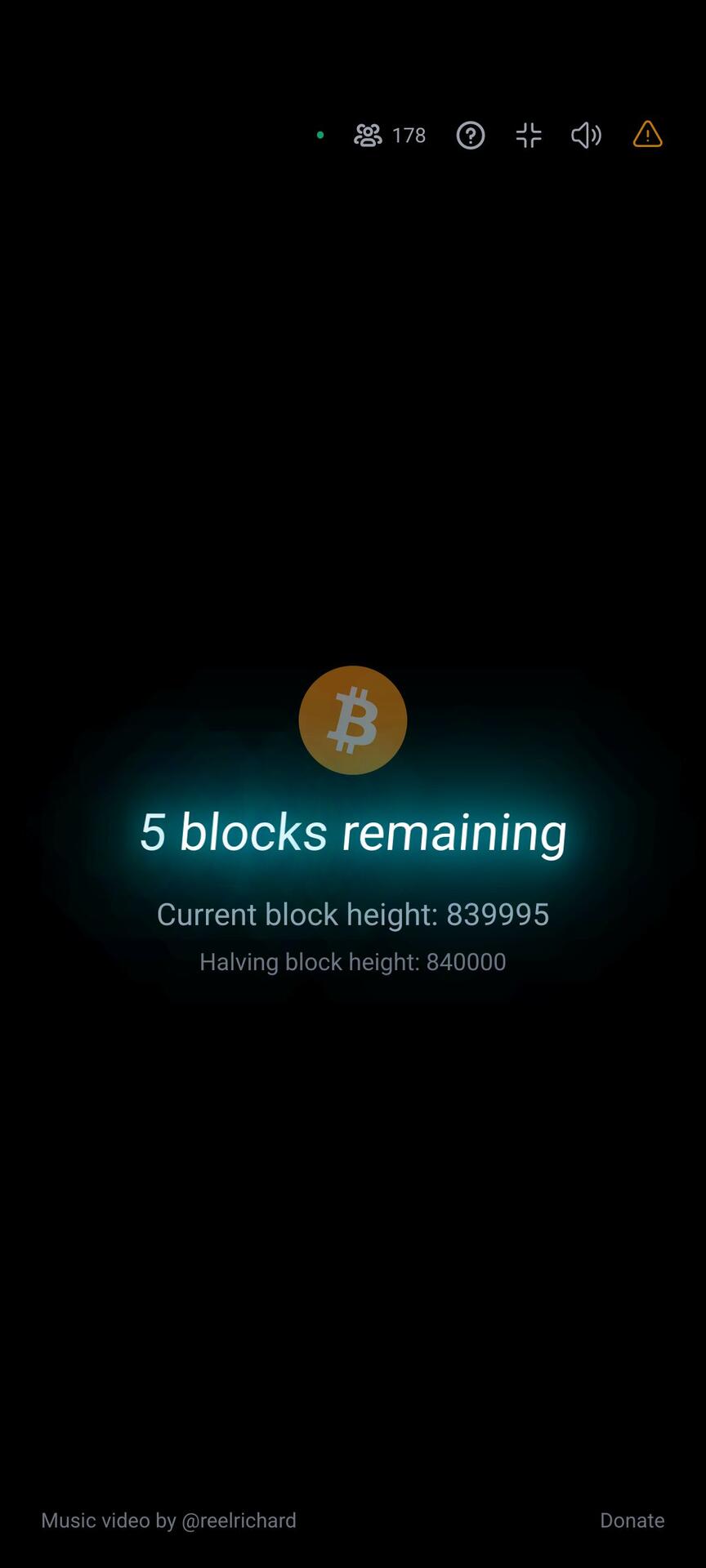

5!

#countdown #countdownstr #Bitcoin #Bitcoinhalving

https://bitcoinhalving.club/

6!

#countdown #countdownstr #Bitcoin #Bitcoinhalving

Blocktrainer - Bitcoin Bildung & News

Halving-Countdown

Verfolge in Echtzeit den Countdown bis zum nächsten Bitcoin-Halving, wenn die Anzahl neuer Bitcoin pro Block halbiert wird!

7!

#countdown #countdownstr #Bitcoin #Bitcoinhalving

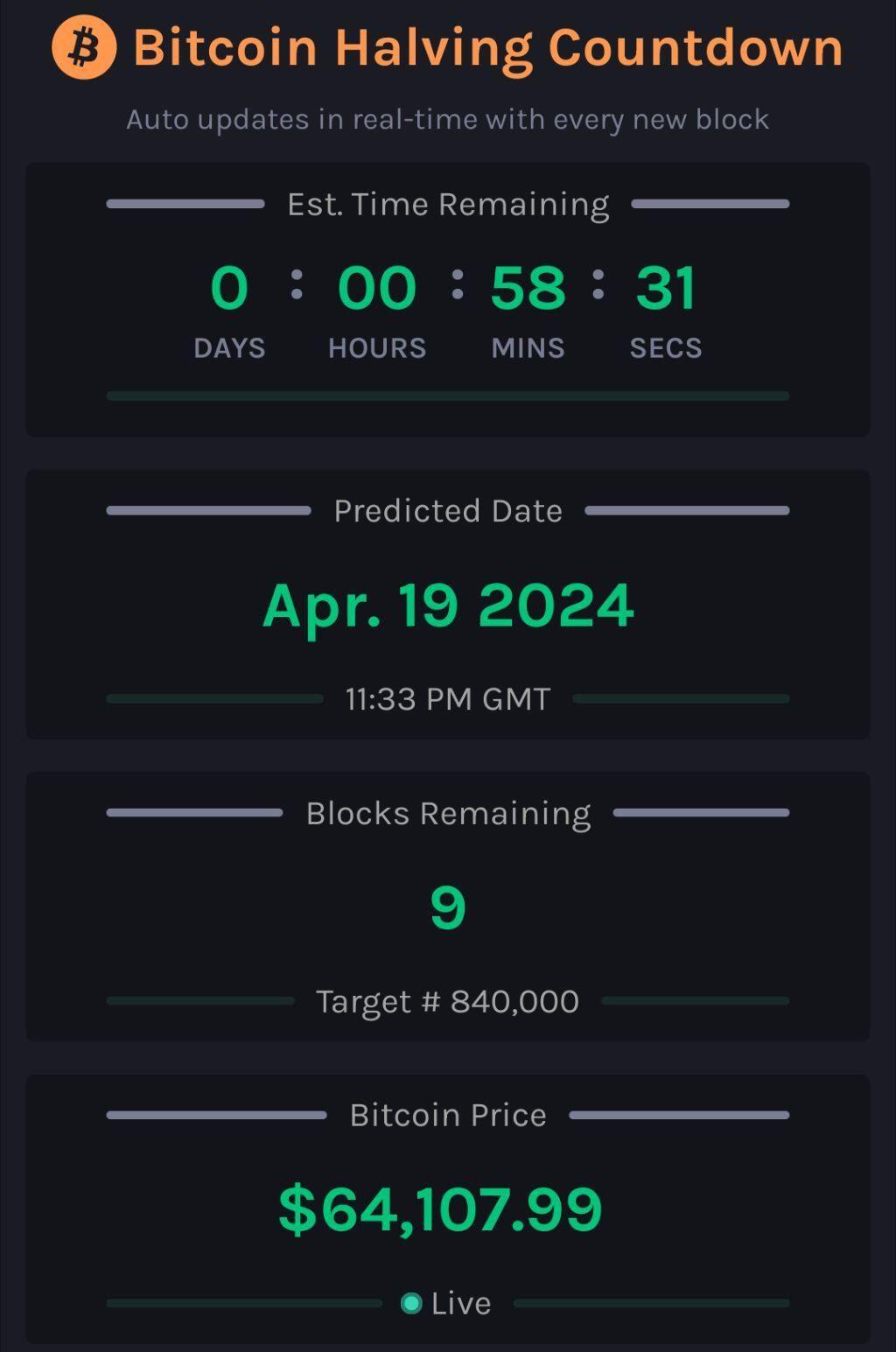

8!

#countdown #countdownstr #Bitcoin #Bitcoinhalving

9!

#countdown #countdownstr #Bitcoin #Bitcoinhalving

10!

#countdown #countdownstr #Bitcoin #Bitcoinhalving

11!

#countdown #countdownstr #Bitcoin #Bitcoinhalving

# [Article 45 Will Roll Back Web Security by 12 Years](https://www.eff.org/deeplinks/2023/11/article-45-will-roll-back-web-security-12-years)

DEEPLINKS BLOG

By Jacob Hoffman-Andrews

November 7, 2023

---

The EU is poised to [pass a sweeping new regulation](https://last-chance-for-eidas.org/), eIDAS 2.0. Buried deep in the text is Article 45, which returns us to the dark ages of 2011, when certificate authorities (CAs) could collaborate with governments to spy on encrypted traffic—and get away with it. Article 45 forbids browsers from enforcing modern security requirements on certain CAs without the approval of an EU member government. Which CAs? Specifically the CAs that were appointed by the government, which in some cases will be owned or operated by that selfsame government. That means cryptographic keys under one government’s control could be used to intercept HTTPS communication throughout the EU and beyond.

This is a catastrophe for the privacy of everyone who uses the internet, but particularly for those who use the internet in the EU. Browser makers have not announced their plans yet, but it seems inevitable that they will have to create two versions of their software: one for the EU, with security checks removed, and another for the rest of the world, with security checks intact. We’ve been down this road before, when export controls on cryptography meant browsers were released in two versions: strong cryptography for US users, and weak cryptography for everyone else. It was a fundamentally inequitable situation and the knock-on effects set back web security by decades.

The current text of Article 45 requires that browsers trust CAs appointed by governments, and [prohibits browsers from enforcing any security requirements](https://blog.mozilla.org/netpolicy/files/2023/11/eIDAS-Industry-Letter-updated.pdf) on those CAs beyond what is approved by [ETSI](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/ETSI).

In other words, it sets an upper bar on how much security browsers can require of CAs, rather than setting a lower bar. That in turn limits how vigorously browsers can compete with each other on improving security for their users.

This upper bar on security may even ban browsers from enforcing [Certificate Transparency](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Certificate_Transparency), an IETF technical standard that ensures a CA’s issuing history can be examined by the public in order to detect malfeasance. Banning CT enforcement makes it much more likely for government spying to go undetected.

Why is this such a big deal? The role of a CA is to bootstrap encrypted [HTTPS](https://www.eff.org/encrypt-the-web) communication with websites by issuing certificates. The CA’s core responsibility is to match web site names with customers, so that the operator of a website can get a valid certificate for that website, but no one else can. If someone else gets a certificate for that website, they can use it to intercept encrypted communications, meaning they can read private information like emails.

We know HTTPS encryption is a barrier to government spying because of the NSA’s famous “[SSL added and removed here](https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/national-security/nsa-infiltrates-links-to-yahoo-google-data-centers-worldwide-snowden-documents-say/2013/10/30/e51d661e-4166-11e3-8b74-d89d714ca4dd_story.html)” note. We also know that misissued certificates have been used to spy on traffic in the past. For instance, in 2011 [DigiNotar was hacked](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/DigiNotar) and the resulting certificates used to intercept emails for people in Iran. In 2015, [CNNIC issued an intermediate certificate](https://slate.com/technology/2016/12/how-the-2011-hack-of-diginotar-changed-the-internets-infrastructure.html) used in intercepting traffic to a variety of websites. Each CA was subsequently [distrusted](

Distrusting a CA is just one end of a spectrum of technical interventions browsers can take to improve the security of their users. Browsers operate “root programs” to monitor the security and trustworthiness of CAs they trust. Those root programs impose a number of requirements varying from “how must key material be secured” to “how must validation of domain name control be performed” to “what algorithms must be used for certificate signing.” As one example, certificate security rests critically on the security of the hash algorithm used. The [SHA-1 hash algorithm](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/SHA-1), published in 1993, was considered not secure by 2005. NIST disallowed its use in 2013. However, CAs didn't stop using it until 2017, and that only happened because one browser made SHA-1 removal a requirement of its root program. After that, the other browsers followed suit, along with the [CA/Browser Forum](https://cabforum.org/).

The removal of SHA-1 illustrates the backwards security incentives for CAs. A CA serves two audiences: their customers, who get certificates from them, and the rest of the internet, who trusts them to provide security. When it comes time to raise the bar on security, a CA will often hear from their customers that upgrading is difficult and expensive, as it sometimes is. That motivates the CA to drag their feet and keep offering the insecure technology. But the CA’s other audience, the population of global internet users, needs them to continually improve security. That’s why browser root programs need to (and do) require a steadily increasing level of security of CAs. The root programs advocate for the needs of their users so that they can provide a more secure product. The security of a browser’s root program is, in a very real way, a determining factor in the security of the browser itself.

That’s why it’s so disturbing that eIDAS 2.0 is poised to prevent browsers from holding CAs accountable. By all means, raise the bar for CA security, but permanently lowering the bar means less accountability for CAs and less security for internet users everywhere.

The text isn't final yet, but is subject to approval behind closed doors in Brussels on November 8.

Mozilla Security Blog

Distrusting New CNNIC Certificates – Mozilla Security Blog

Last week, Mozilla was notified that a Certificate Authority (CA) called CNNIC had issued an unconstrained intermediate certificate, which was subs...

> Encryption should be enabled for everything by default, not a feature you turn on only if you’re doing something you consider worth protecting.

>This is important. If we only use encryption when we’re working with important data, then encryption signals that data’s importance. If only dissidents use encryption in a country, that country’s authorities have an easy way of identifying them. But if everyone uses it all of the time, encryption ceases to be a signal. No one can distinguish simple chatting from deeply private conversation. The government can’t tell the dissidents from the rest of the population. Every time you use encryption, you’re protecting someone who needs to use it to stay alive. — Bruce Schneier

---

---

---

# [Why We Encrypt](

Encryption protects our data. It protects our data when it’s sitting on our computers and in data centers, and it protects it when it’s being transmitted around the Internet. It protects our conversations, whether video, voice, or text. It protects our privacy. It protects our anonymity. And sometimes, it protects our lives.

This protection is important for everyone. It’s easy to see how encryption protects journalists, human rights defenders, and political activists in authoritarian countries. But encryption protects the rest of us as well. It protects our data from criminals. It protects it from competitors, neighbors, and family members. It protects it from malicious attackers, and it protects it from accidents.

Encryption works best if it’s ubiquitous and automatic. The two forms of encryption you use most often—https URLs on your browser, and the handset-to-tower link for your cell phone calls—work so well because you don’t even know they’re there.

Encryption should be enabled for everything by default, not a feature you turn on only if you’re doing something you consider worth protecting.

This is important. If we only use encryption when we’re working with important data, then encryption signals that data’s importance. If only dissidents use encryption in a country, that country’s authorities have an easy way of identifying them. But if everyone uses it all of the time, encryption ceases to be a signal. No one can distinguish simple chatting from deeply private conversation. The government can’t tell the dissidents from the rest of the population. Every time you use encryption, you’re protecting someone who needs to use it to stay alive.

It’s important to remember that encryption doesn’t magically convey security. There are many ways to get encryption wrong, and we regularly see them in the headlines. Encryption doesn’t protect your computer or phone from being hacked, and it can’t protect metadata, such as e-mail addresses that need to be unencrypted so your mail can be delivered.

But encryption is the most important privacy-preserving technology we have, and one that is uniquely suited to protect against bulk surveillance—the kind done by governments looking to control their populations and criminals looking for vulnerable victims. By forcing both to target their attacks against individuals, we protect society.

Today, we are seeing government pushback against encryption. Many countries, from States like China and Russia to more democratic governments like the United States and the United Kingdom, are either talking about or implementing policies that limit strong encryption. This is dangerous, because it’s technically impossible, and the attempt will cause incredible damage to the security of the Internet.

There are two morals to all of this. One, we should push companies to offer encryption to everyone, by default. And two, we should resist demands from governments to weaken encryption. Any weakening, even in the name of legitimate law enforcement, puts us all at risk. Even though criminals benefit from strong encryption, we’re all much more secure when we all have strong encryption.

---

Schneier on Security

Why We Encrypt - Schneier on Security

Encryption protects our data. It protects our data when it’s sitting on our computers and in data centers, and it protects it when it’s...

Rachel Tobac - Security, hackers and password

# [Code Vulnerabilities Put Proton Mails at Risk](https://www.sonarsource.com/blog/code-vulnerabilities-leak-emails-in-proton-mail/)

### Paul Gerste

### VULNERABILITY RESEARCHER

September 5, 2023

12 MIN READ

-----

## Key Information

__Key Information__

+ In June 2022, the Sonar Research team discovered critical code vulnerabilities in multiple encrypted email solutions, including Proton Mail, Skiff, and Tutanota.

+ These privacy-oriented webmail services provide end-to-end encryption, making communications safe in transit and at rest. Our findings affect their web clients, where the messages are decrypted, mobile clients were not affected.

+ The vulnerabilities would have allowed attackers to steal emails and impersonate victims if they interacted with malicious messages.

+ Nearly 70 million users were at risk on Proton Mail alone.

+ Thanks to our report, the issue has been fixed and there are no signs of in-the-wild exploitation.

-----

#security #news #protonmail #tutanota #skiff #email