I think I'm one of the slopsters, amongst other things trying to create accurate measurements of harm to unarmed people around the globe.

Then a enablement matrix, so it maps culpability. Expected harm if continued and life giving measures proposals.

No coding experience other than dabbling over a few months.

Predictive modeling maths, is beyond me, want an accepted calibrated method that is uncontroversial but seeks to give a true reflection.

Many measurements are contested and reality gets missed.

Dusty

npub1sqlt...flpk

Raising the vibration of the light within all. Mutual aid with love. Endeavour to liberate. Community empowerment facillitator. Magic.

Bahá’í institutions are saying (substance, not rhetoric)

Official Bahá’í bodies and representatives (notably at the UN level) have consistently expressed the following positions in relation to unrest and repression in Iran:

Deep concern for loss of life, mass arrests, and repression, regardless of political framing.

Calls for restraint by authorities, protection of civilians, and respect for due process.

Emphasis on dialogue and inclusion, especially addressing long-standing grievances (economic, social, and cultural).

Rejection of collective punishment, including internet shutdowns, intimidation of families, and targeting of minorities.

These statements are careful, measured, and avoid inflammatory language by design.

Particular sensitivity: minorities and conscience

Bahá’í commentary often highlights a broader pattern:

Societies that criminalize conscience—whether religious belief, peaceful dissent, or independent thought—tend toward recurring unrest.

The long persecution of Bahá’ís in Iran is cited not to claim exceptionalism, but as evidence of systemic intolerance that ultimately harms the whole society.

In this framing, current events are not an anomaly but part of a deeper moral and governance crisis.

Thanks, a great read, as a non programmer, playing around, I find the conceptualisation of ideas of llm models great and pulling up some research. As a pauper, it has made idea progression better though exquisite control takes time and often get caught in loops. I was beginning to find the limitations and that it was quicker in some instances to mix it up. As a stulator and drafting it's good. Finished article, long form content, quite poor.

Must read, enjoying the articles folk are writing

View article →

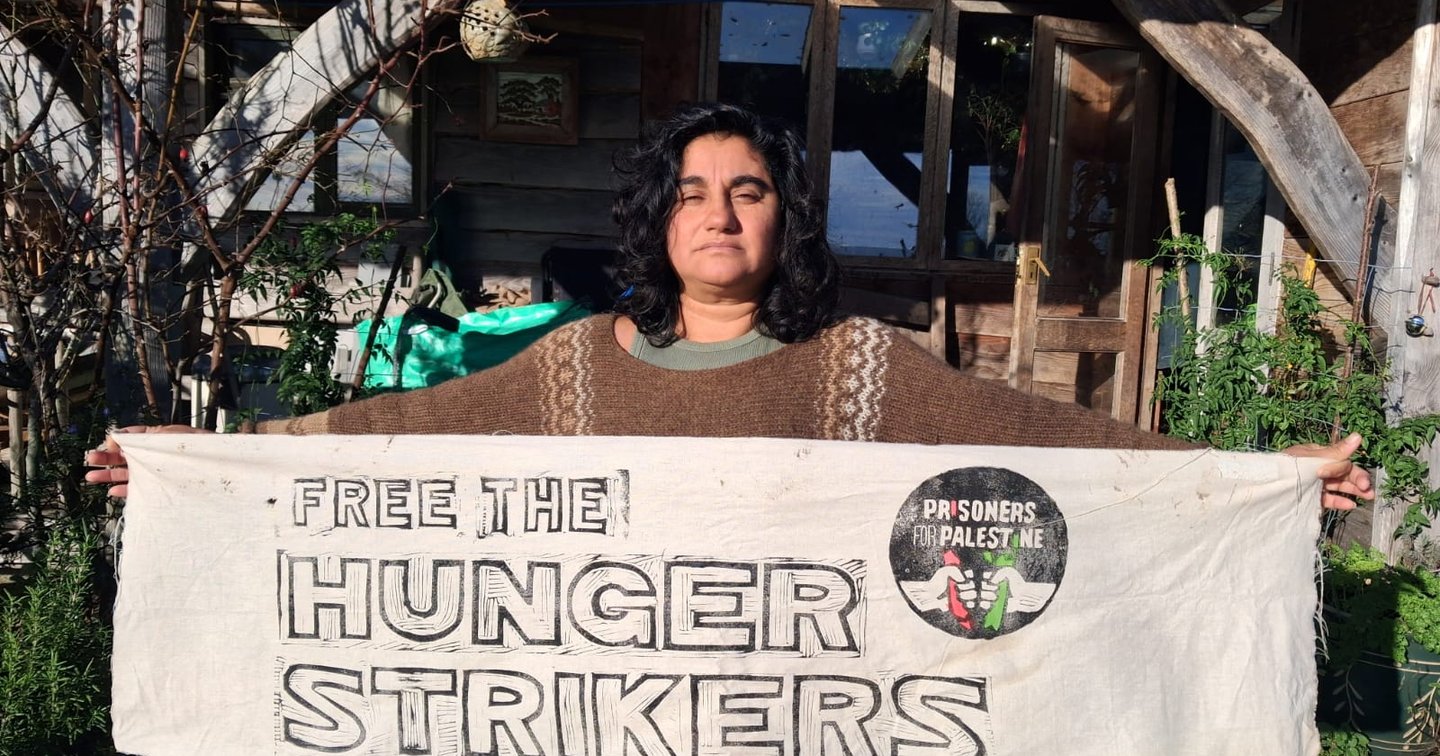

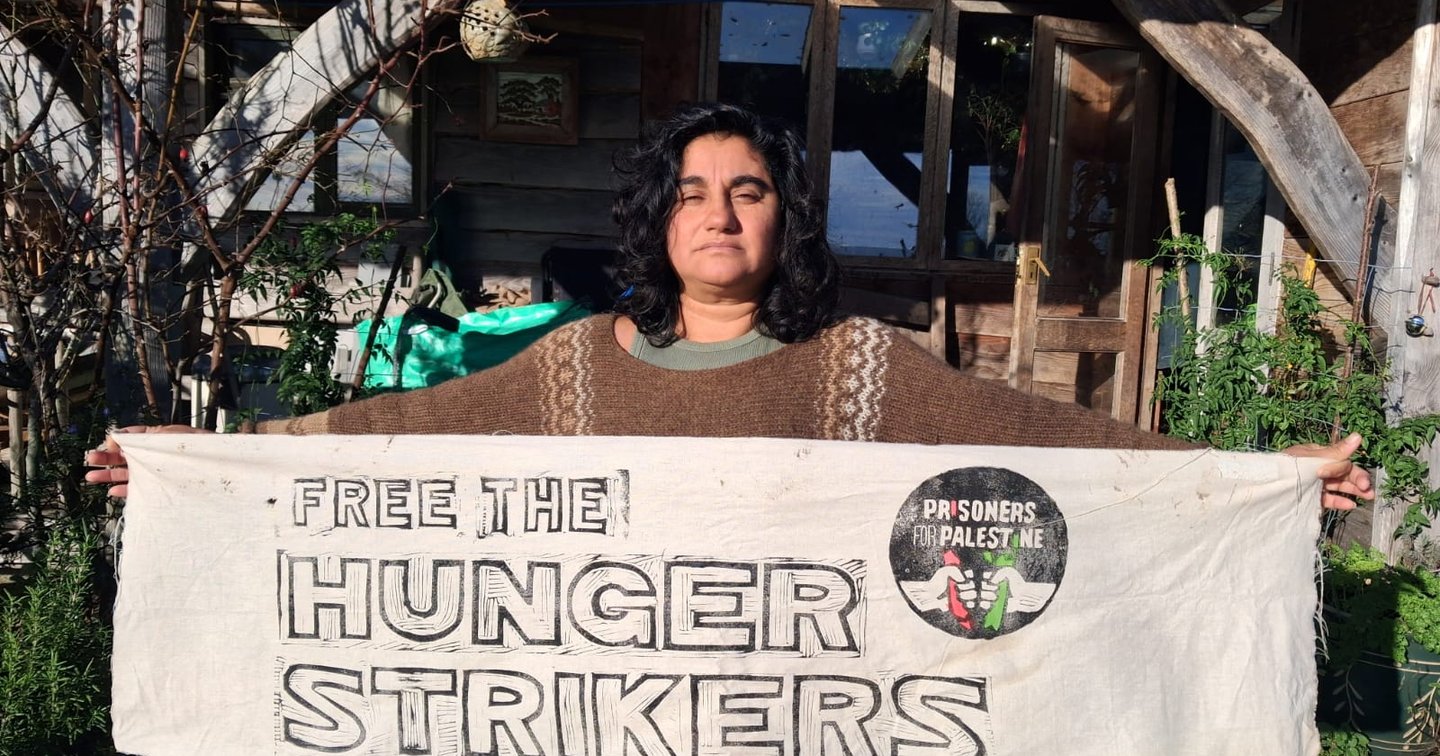

We held all eight Hunger Strikers in the light this morning at 8am.

Here is a loving plea for sanity from another network (Land Workers Alliance) sharing news of Amu in HMP Bronzefield

Fivepenny Farm

Solidarity with the hunger strikers | Fivepenny Farm

Jyoti Fernandes speaking in solidarity with Amu and the Palestine Action hunger strikers

Vigil happening all day today outside BBC, London till 6pm

Some hunger strikers are now hospitalised and close to death.

“In the worst crisis humanity has ever faced, the government chose to legislate to silence dissent, rather than implementing policies to avert disaster. People of conscience are imprisoned, while others remain free to continue destroying our life support systems. “

Just Stop Oil – No More Oil and Gas

Four Just Stop Oil supporters jailed for up to 30 months for M25 gantry action while two walk free – Just Stop Oil

Six Just Stop Oil who were denied all legal defences during their trial were today given sentences of up to 30 months at Southwark Crown Court for ...

A vigil was held outside Bronzefield prison where two people are on hunger strike whilst being held on remand for taking preventative actions against crimes against humanity.

Leaflets were handed out and in discussion with some of the people working in prison, they had no idea there was a hunger strike happening.